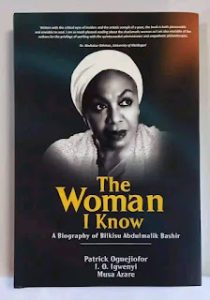

Book: The Woman I Know: A Biography of Hajiya Bilkisu Abdulmalik Bashir, by Patrick Oguejiofor, I.O. Igwenyi and Musa Azare

William Shakespeare, one of the greatest masters of the theatre, often resorted to the stage to draw striking images to express his deeply-felt philosophies about life. In his great play, As You Like it, he penned the immortal words about the world being ‘a stage, and all the men and women merely players.’

Continuing with this imagery of the theatre in his timeless tragic play, Macbeth, Shakespeare sees life or man as a player upon the stage. It behoves the historian or biographer, as time’s chronicler, to record with fidelity to truth the parts played by these players, their entrances and exits. What role has Hajiya Bilkisu Abdulmalik Bashir as a socio-political being and character on the world’s stage played – and is still playing – in the course of her earthly journey through life? Did she deliver her lines with proper elocution and precision or merely strutted and fretted her hour upon the amphitheatre called life?

This is what Patrick Oguejiofor et al sought to do in their book, The Woman I Know. The question is to what extent have they succeeded or failed? Subdivided into two parts, the book chronicles the journey of Hajiya Bilkisu Abdulmalik Bashir from birth, childhood, education, career right up to her retirement.

Part One dwells on the formative years of her life. Born into the family of Alhaji Abubakar Ajanah and Hajiya Zainab, the eldest daughter of the renowned diplomat and statesman, Mallam Abdulmalik, Hajiya Bilkisu’s early years were spent with her maternal grandfather. From Okeneba, a suburb of Okene, the place of her birth, she moved to London with her grandfather who was Nigeria’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom where she began her formal education in 1963 at St. Peter’s School, a primary school. This was not to last owing to the sudden transfer of her grandfather to France in 1966 as Nigeria’s first Ambassador to that country.

Needless to say, little Bilkisu followed her grandfather, which necessitated her changing from St. Peter’s School in London to a new school in Paris. Unfortunately, the unexpected death of the patriarch, Mallam Abdulmalik, while on a visit to his hometown of Okene in 1969 brought her stay in France to an abrupt end, leaving her with no option but to continue her education in Nigeria with Adeola Model School, a private boarding school in Offa, Kwara State. She described this period in her life as ‘the worst year of my life (1970) and the worst punishment anybody could give me’ (p. 31).

Happily, her stay at that school was brief, and one year later she completed her primary school education, and was admitted into the Queen Elizabeth School, Ilorin, a school that she recalled with fond reminiscences.

Five years after sitting for the West African School Certificate Examinations, she proceeded to the School of Basic Studies (SBS) of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and subsequently got admission to study law at the same university. Upon graduation in 1979 after obtaining a law degree, she was admitted into the Nigerian Law School, Lagos, and was called to the Nigerian Bar a year later.

Part One closes with her nearly two decades’ engagement with the Kano State government under the Kano State Housing Corporation in the wake of her completion of the one-year obligatory National Youth Service Corps (NYSC). One significant thing apparent in Hajiya Bilkisu’s rollercoaster ride through childhood to adulthood with a gainful employment with the Kano State government is the amazing kind of privileges that she and her close friends enjoyed in a generation that could rightly be called lucky.

Though born several decades after the Chinua Achebe generation, Hajiya Bilkisu enjoyed the lofty benefits accruable to what Achebe tagged the ‘Lucky Generation’ in his book, There was a Country. While awaiting her Bar Final Examination result, Hajiya Bilkisu travelled to London to stay with Aunt Winnie’s friend for her holiday, but it was not only her as ‘several Bilkisu’s friends and former course mates at the Law School were also in London then’ (p. 60).

It was a generation where ‘there were more jobs than job seekers’ (p. 78) which explained her hesitancy in accepting any of the two jobs from two different companies before finally opting for a government job with Kano State Housing Corporation.

According to Shakespeare in his play, Twelfth Night, ‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.’ Hajiya Bilkisu’s life has however shown that it is not enough to achieve greatness by virtue of one’s birth into a noble family nor by mere membership of the ‘Lucky Generation’ of Nigeria’s history who had greatness thrust upon them by reason of their acquisition of the golden fleece of a university degree, dint of hard work and grit must be added to it to achieve greatness. She does not belong to the group of people whose ‘palm-kernels were cracked for them by a benevolent spirit’, to quote Achebe’s great novel, Things Fall Apart, her tireless input was vital for the greatness she achieved in life and career.

A biography is essentially the history of a person whose life cannot be chronicled to the exclusion of the historical realities of the subject’s era. This book is not an exemption, and from it we could see when, as Achebe would say, the rain began to beat us as a nation.

Part Two opens with Hajiya Bilkisu’s meteoric rise to national prominence from the relative obscurity of a legal adviser-cum-secretary to Kano State Housing Corporation to head two Federal Executive bodies at the same time, namely, the National Judicial Council (NJC) and the Federal Judicial Service Commission (FJSC) created by the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) with the Chief Justice of Nigeria serving as their Chairman.

As the pioneer secretary of both bodies, her administrative acumen and leadership style came to the fore. She waded intrepidly through the murky waters of public office politics and intrigues, unscathed.

The glowing testimonies of seven out of the eight different Chief Justices of Nigeria (CJNs) that she served under attest to this. There is a unanimity by board members and staff of the two bodies who worked under her as well as reverred justices of the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court who had had contact with her in the course of her duties that she is a woman of proven integrity, probity, forthrightness, fairness and firmness, a great achiever adept at conflict management with zero-tolerance to compromise. Her handling of staff matters, welfare and the unavoidable wrangling made her a darling among her subordinates. She was aboveboard in the discharge of her duties especially in the award of contracts based on merit without kickbacks or gratification. Her being a stickler for due process was to be tested when the Federal Judicial Service Commission wanted to acquire a suitable plot of land to build a liaison office and an examination hall in Lagos.

One of the sale proposals was from her husband but as the topflight astute administrator which she had demonstrated so far, she turned it down, and ‘in its place picked the one which, in her own consideration, was better and cheaper, taking into consideration what the Commission needed’ (p. 219).

Her benchmark for equality in dealing with everyone without fear or favour was perhaps inspired by Lord Alfred Denning’s holding that: ‘You must not discriminate against a man because of his colour or of his race or of his nationality, or of “his ethnic or national origins.”‘ (See the UK Court of Appeal case of Mandla (Sewa Singh) v Dowell Lee [1983] QB 1). As a result, she was a detribalised administrator par excellence, who placed premium on efficiency and reliability far above primordial sentiments like geo-political, ethno-religious factors as evident in the appointment of Mr Akinwumi Aina ‘to replace the outgoing Head of Administration, Mr Lawal Mani’ (p. 231).

During her administration, laudable projects such as remodelling the building headquarters of Federal Judicial Service Commission, its liaison office and an examination hall in Lagos in addition to the robust staff welfare and self-improvement packages and the provision of accommodation for staff members of the Commission who eventually became by reason of this foresight and dynamism house owners in Abuja pursuant to the monetisation policy under President Olusegun Obasanjo (p. 221).

It was in recognition of this sterling records that she was decorated with numerous awards and honours from reputable organisations and agencies, including the National Honours Award of Officer of the Order of the Niger (OON) in 2009 by Nigeria’s former President, Dr. Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, and the conferment of the title ‘Onyi Oniroye Anebro’, meaning, Mother of Wisdom, by her kinsmen, the socio-cultural Ebira group called Dynamic Ebira Friends Club of Nigeria in 2016.

One interesting feature of this book on the life of this czar of judicial independence in Nigeria is that lawyers and non-lawyers alike could easily visualise how the National Judicial Council and the Federal Judicial Service Commission operate in action in checkmating executive incursion. It has effortlessly taken these two bodies from mere theoretical federal judicial bodies created by the constitution with a view to safeguarding the independence of the judiciary with working knowledge and practicality.

On the home-front, Hajiya Bilkisu was a happily married woman to Engineer Mohammed Bashir Karaye whom their paths had earlier crossed during her days with the Kano State Housing Corporation, with the latter then her boss. Their love may have budded in Kano but before it graduated into marriage years later, both of them had left the Kano State service, she for a higher national call with the Federal Government.

Despite the initial opposition by his people on the basis of stereotyping her Ebira ethnic group, the two love birds weathered this incipient storm and got married, a marriage which was fated not to last, and in 2006, he succumbed to an illness.

She immortalised him years later through the Engineer Mohammed Bashir Karaye Prize for Hausa Literature in collaboration with the Engineer Mohammed Bashir Karaye Foundation and the Abuja Chapter of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) where prizes were given for excellence in indigenous writing with a view to encouraging writers to preserve their mother tongues.

The reader is regaled with how she has been supportive of her late husband’s family several years after his demise and the beautiful relationship that still flourishes between her and other wives including her late husband’s mother. As an embodiment of love, instances of her extravagant generosity to her subordinates and family members and foster children whom she took under her altruistic wings abound in this work.

The reader is pleasantly struck by Hajiya Bilkisu’s disarming honesty, and invariably the writers’ faithfulness to the available facts before them. For example, when her grandmother Hajiya Amina confronted her as a young schoolgirl whether she had a short temper as people told her, she replied in the affirmative, and recalled further that, ‘I told her the truth. There was no point in pretending’ (p. 36). The fact that she has ‘a short fuse’ (p. 206) that could ‘easily snap under provocation’ (p. 47} is well documented with the extenuating quality that ‘her temper hardly lasted’ (p. 206).

It was with the same humility and sincerity that the teething problems she faced in her job as Federal Judicial Service Commission boss such as ‘leakages of official secrets’ (p. 129) and the high points were outlined in a rather balanced manner. The advantage of divulging no-holds-barred truth is the verisimilitude it invests the work with.

The writers did not paint Hajiya Bilkisu as a faultless angel but a flesh-and-blood being with all the frailties that all mortals are heirs to. The snag, however, is the unavoidable propensity to sometimes carry this honesty to the level of innocence like the subject’s admission of influencing her NYSC posting to Kano State when she recounted, ‘I won’t lie to you! Yes, we lobbied’ (p.62). The implication of such unashamed confessions is that the unwary reader unacquainted with her antecedents may conclude that she is not impervious to the backdoor tactics that most Nigerians cannot be acquitted of.

In the business of book publishing, no matter how seminal the contents of a book may lay claim to, the quality of the physical product cannot be dismissed with a wave of the hand. It is the first thing that arrests the eyes of a would-be reader enough to motivate him to want to part with his hard-earned money. In consequence, how a book is produced invariably affects the sales. No doubt, there is a truism in the cliché that first impression matters a lot, and the publishers, foolhardy enough to ignore this, do that at their peril.

As regards this work, can one say that the final product satisfies this criterion? A cursory look at the book will answer this question.

To begin with, the cover design is eye-catching, adorned with the photograph of a benign-faced Hajiya Bilkisu Abdulmalik Bashir sporting a white dress and a white head-tie both in sync with the array of dark, blue and mahogany colours in the background. Also, the blurbs are succinct, aptly couched without the usual pedantic, too revealing obsequiousness.

Printed on high-quality paper, with a gallery of glossy photographs sandwiched between major sections of the book, which are capable of taking those familiar with the subject down the memory lane, the early family tree beginning from the nostalgia-inspiring pictures of a young Bilkisu, her grandparents’ especially the fabled patriarch Mallam Abdulmalik, including her parents and their siblings and other members of the extended family, her journey through primary schools as shown on group class photographs, before culminating in the galaxy of stars which form the pantheons in the hallowed hall of the Nigerian judiciary, amongst several others, depict pictorially the history of her life and career.

One interesting aspect of the work is that at each stage of the subject’s life the reader gets to know the political climate of Nigeria as a backdrop to the narrative. The palpably tense and awkward situation that her grandfather Abdulmalik and the rest of the family found themselves in France when the Civil War broke out in Nigeria with the host nation supporting the breakaway Republic of Biafra was vicariously felt by the reader at pages 24 -25. And while Nigeria was transiting from military dictatorship to civil rule in 1979, she was a Nigerian Law School student in Lagos at pages 53-54.

Perhaps the event that was the scariest to her because it affected her personally happened during her one-year mandatory national service in Kano in 1982 when the violent Maitatsine religious uprising broke out. She found herself enmeshed in the unpalatable incident where she was ordered by a police officer at one of the numerous checkpoints scattered all over the city to come down from a taxi she boarded on the most preposterous suspicion of being a member of the sect. This wild and unfounded allegation was enough to make her cry copiously.

Her NYSC identity card and the one from the Kano State Ministry of Justice where she was posted as her primary place of assignment had to come to her aid and bailed her out of that embarrassing situation.

The novelistic approach adopted in the work, laced with apt description of places and historical locales, garnished with recollected exchanges of the dramatis personae which were rendered in realistic dialogues as well as testimonies of those who had had contact with the subject either officially or unofficially all add to the compelling readability of the work.

Written in a simple and lucid language, the largely omniscient narrative style used, interspersed with occasional first person narrator ‘we’ to reflect the plurality of the authorship, somewhat morphed incongruously into the first person singular ‘I’ in the last three but one chapter, and carried the same intensity and tone of voice as the one used in the Introduction. This perhaps raises the issue of a misnomer in the title as the story is told by a troika and not a single writer. Despite the frequent complaint of ‘space constraints’ owing probably to the enormity of what to write about so great a woman, efforts to circumvent this seemed not to be spiritedly made and in consequence the work sags a little with needless overweight.

With a Preface presumably by the authors and a Foreword by Honourable Justice Walter Samuel Nkanu Onoghen, GCON, former Chief Justice of Nigeria and Chairman, Federal Judicial Service Commission at the opening pages, the inclusion of a rather prolix and impassioned Introduction is a superfluity which the biography would have fared beautifully well without. Sometimes the unrelenting harping on the subject’s virtues in superlative terms could be jarring on the reader’s nerves. The expression of emotion in art that is sensationalised has the same wilting effect as a biography allowed to strain loose from its leash, and drift into near deification.

The opposite aim, alas, is achieved as its veracity is tempered. Again, as seemingly exhaustive as the portrayal of the life and career of the subject is in the work, there seems a lacuna that the three-page epilogue at chapter twenty-seven titled, ‘Afterwords’ dated March 26, 2022 does not mitigate. Apart from the silence on her personal love life on whether she had found a heartthrob since the demise of her beloved husband in 2006, there is an inexplicable hiatus about her life five years after her retirement from public service as though her life came to a standstill upon her drawing curtains on active government service.

Without a shadow of doubt, The Woman I Know is a well-researched, riveting read distilled from in-depth, first-hand intimacy which only insiders like the writers who had known the subject over the years could undertake with a resounding success.

From the inspiring life and career of Hajiya Bilkisu, young lawyers at the dawn of their career are exposed to the limitless opportunities that the legal profession offers, and the need to take a stand as early as possible as to what area of law practice they are ‘cut out for’ (p. 78). It was this early vision that guided the career path in the legal profession for Hajiya Bilkisu and ultimately paved the way for her meritorious service and fulfilment in life.

* Isaac Attah Ogezi, a legal practitioner, poet, playwright, literary essayist and short story writer, lives and practises law in Keffi, Nasarawa State