Book Review:

TITLE: Babingo the Noble Rebel

AUTHOR: Moussibahou Mazou

PUBLISHER: Sub-Saharan Publishers, Legon-Accra, Ghana

At the last count, there were 48,400,000 fictional accounts on the theme of colonialism globally. These include ‘Things Fall Apart’ by Chinua Achebe, ‘Midnight’s Children’ by Salman Rushdie, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and ‘Kindred’ by Octavia E. Butler, among others.

In addition, on December 14, 1921, the first book by a black author to win France’s most prestigious literary prize also forced the country to confront its brutal colonial record. That year, The Prix Goncourt, France’s top literary award, had gone to René Maran, a French Guyanese colonial administrator in Ubangui-Shari — what is today the Central African Republic.

Maran was the first black winner of the then 18-year-old award. But as civil rights and anti-colonial movements were stirring, it was the content of Maran’s novel that truly set off tremors on both sides of the Atlantic.

“You build your realm on dead bodies,” wrote Maran in the preface to the book, Batouala. “You are living a lie. Everything you touch you consume.”

A searing indictment of French colonialism in central Africa, the book was an insider’s account that forced France to confront the reality of its “civilizational” mission, much as Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ had lifted the veil on Belgian brutality in the Congo two decades earlier.

The French Parliament debated the book, with some accusing Maran of defamation and others arguing that he had exposed exploitation.

Several French writers criticized the Académie Goncourt, with some predicting Batouala would soon be forgotten.

They were wrong. Maran’s own career as a colonial administrator ended soon after, and faced with threats of retribution, he returned to Paris in 1923.

But he became the “African point of reference” for writers of the Harlem Renaissance, according to the late French expert on African-American studies, Michel Fabre. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about Maran and Batouala in The Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, while a young Ernest Hemingway, writing in Paris for the Toronto Star Weekly, called the book “great art.”

Just when many thought that the subject of colonialism would go away, Moussibahou Mazou, in his 2021, 22-chapter, 273-page novel, takes us back to the ageless subject with its multiple ripple effects of cultural clash, religious ambivalence and the advocacy for the mainstreaming of indigenous African languages into the curriculum of African countries.

In the racy and pulsating narrative set in the 1950s, Paul Makouta, a ‘Frenchified and Elitist native’ of the now independent Congo-Brazzaville, thought he was preparing his only son, Alex Babingo, and his siblings to step into the shoes of the country’s French colonial masters when he insisted that his children must communicate exclusively in French.

While it may be justifiable for Paul Makouta to project into his son his own ambitions, particularly those he had been unable to achieve himself, little did he know that by alienating his offspring from their native language and by extension their culture, he was hauling the family into an abyss from which they would find difficult to escape.

To further perfect his plan of educating his children according to European mode of expression and thought in order to make it easy for them to snatch power from the French colonialists, Makouta sent Alex to France for his secondary school and university education.

In addition, rather than allowing his son to come home regularly for holidays, Papa Makouta sent Alex to various summer camps in France where he perfected his French language.

Unknown to Papa Makouta, Alex had secretly learnt to speak Kituba, a Congolese native language through one of his classmates, Tessa, in the city of Pointe Noire where the family lived.

Even at this, Alex still found it difficult to express himself very well in his native language to the extent that he was unable to sing a song in his native language when asked to do so during a concert in his school in France.

The young boy soon became the butt of jokes by his European classmates who couldn’t believe that Alex could not speak his native language.

The shock of the incident jolted Alex to realize the importance of language as the purveyor of culture.

As cultural experts put it: ‘’It is through language that culture is transmitted from one generation to another. When a language dies or goes into extinction, other aspects of culture are likely to go down with it.

Without the indigenous language necessary to promote and sustain their relevance and the transfer of the skills used in creating them, even these objects and ways of life of the people will disappear with time’’.

In his determination to ‘’fight for the incorporation of national languages into our country’s curriculum when it attains full sovereignty’’ without informing his father, Alex changed his course of study from Medicine, which was imposed on him by his father, to Linguistic Studies.

When Papa Makouta discovered that his son had changed his course of study, he cut off his allowance. This left Alex with no choice but to do menial jobs with which he took care of his studies and upkeep.

By turns shocking, passionate, unflinching, bitter and above all, nationalistic, ‘Babingo the Noble Rebel’ sweeps the reader along Babingo’s adventures, which included a love child from his European girlfriend, to his return to his native country to learn the language of his mother’s ethnic group, among other haunting narratives.

We also travelled with Babingo on the railway line called Congo-Ocean Railway from his native Pointe-Noire to the capital city of Brazzaville where his cousins gave him a quick tour of the city before his departure by plane to Paris.

This was followed by another trip through the Parisian subway on to another long train journey to his final destination at Toulouse.

The long journey from Toulouse to Reykjavik in Iceland to see his new born child and his mother was another arduous addition to the young man’s problems.

The train journey took him through Paris, Cologne, Copenhagen, as ‘the powerful Borealis locomotive cut through adverse and foggy winds with great speed, haughtily ignoring the intermediary stations to stop only at Kolding and later at Odense’.

After a train journey of more than twenty-four hours, Babingo began another lap to the distant and isolated country of Iceland.

He covered more than 2,000 kilometres by sea, and another 1,079 nautical miles before reaching Reykjavik where he met the family of his girlfriend and his 12-day-old son whom the 20-year-old man named Didrik Alexson Kikimayo.

A well written book, ‘Babingo’ brims with intriguing, well-developed characters and a fast-paced plot that offers a plethora of surprising traits and turns.

Sometimes engaging, often vibrant and lucid but always powerful, this novel explores the urgent need for the study of indigenous languages. This is because any language that is not written and studied will surely die.

This is why it is necessary to encourage the young ones to speak their mother tongue.

Speaking a language is what primarily keeps it alive while neglecting it may lead to its extinction as is the case with Australia where there is a clear lesson to be learnt about language extinction from Australia where from 200 languages but about 200 years, only about 20 remain till today.

After his hurried departure from his mother’s Odiba village with Ingrid, his European girlfriend and mother of his son, Alex, who by then had changed his name to Intu Ngolo Babingo, was appointed a Deputy Minister of Education in the newly independent Congo Brazaville.

Even though he was later removed from the ministerial position, Babingo finally succeeded in ensuring that his mother’s ethnic language was one of those promoted to the rank of national languages to be taught as compulsory subjects in the country.

The author, however, did not fully resolve the fate of Ingrid and Alex’s baby son who had been left by the mother with her parents in faraway Iceland. Will the couple be reunited after Ingrid’s expulsion from the Congo after the expiration of her visa or will Alex move to Iceland to join his young family?

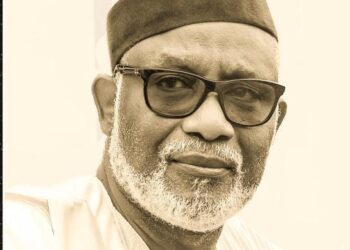

* Dr. Okediran is the President of Pan African Writers Association (PAWA)