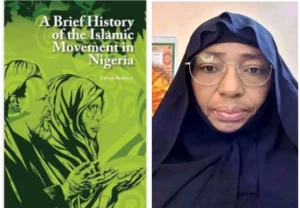

TITLE: A Brief History of the Islamic Movement in Nigeria

AUTHOR: Zeenah Ibraheem

REVIEWER: Usman Oladipo Akanbi

PUBLISHER: Islamic Human Rights Commission

YEAR OF PUBLICATION: 2022

PAGES: 90

It’s always important to have books documenting oppressive tendencies of leadership at every strata of the society, and this perhaps necessitated the interest the Islamic Human Right Commission of the United Kingdom had in this book; the organization in its foreword gave insights into what to expect in the book – within which serious concerns were expressed about the pervasive human right abuses the Islamic Movement in Nigeria organization had suffered in the hands of successive regimes in Nigeria.

As a matter of fact, those who only see the prime mover of the Islamic Movement in Nigeria — Shaikh El Zakzaky, from a distance without having access to the sort of information this book contains, would assume that he is nothing but a rabble rouser. They would erroneously do this without realizing that Shaikh is just someone who is largely impassioned by a burning desire to make the world around him a much better place to live in. And that more importantly, he transmits this zeal to whosoever cares about the promise of an eternal life with the One who created all that’s in heaven and on earth.

The book is segmented into twelve short chapters largely detailing the travails of the leader of the Islamic Movement in Nigeria organization, as well as that of his family and followers alike. It sufficiently chronicles their collective struggle against the high-handedness of supposedly oppressive regimes in Nigeria.

In the first chapter, Zeenah Ibraheem avails to us an enthralling portrait of Sheikh Ibrahim Yaqoub Zakzaky, who, perhaps more than any other Muslim cleric, had been entangled in an intractable struggle with the different leaderships of this country over the last fifty years. As Zeenah reflects in her book, there is much to admire about Shaikh Ibrahim Yaqoub Zakzaky other than the negative narrations his traducers want the world to believe. To this effect, she feeds us with descriptions of his early childhood days, his educational background and scholarly sojourns, both at the famous School for Arabic studies, Kano and the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Economics in 1979. Indeed, his accomplishments, both in the spheres of Islamic and western education, must have largely influenced his activism within the Islamic faith.

His profound activism within the Muslim Student Union, his involvement with the Shia group and the commencement of his long-running battle with the authorities of the Nigerian Federation are also briefly related. The author does not fail to let us into the reasons why she agreed to marry Shaikh after an initial reluctance, a marriage which she evidently never regretted; her deep affection for him is deeply referenced in this book. The author concludes chapter one with accounts of her husband’s deep devotion to the worship of Almighty Allah, and of course, the magnanimous relationship he maintained with his nuclear and extended family members.

In Chapter Two, the author relates the antecedents which led to the formation of the movement. Capitalizing on his position as the Vice President of the Muslim Student society (MSS) of Nigeria and of course programmes under his watch like the Islamic Vacation Courses, Shaikh drew a lot of admirers to himself; the formation of the External Enlightenment Department was one fait accompli, as most members of this department made up the bulk of the early converts to the Islamic Movement.

Shaikh was deeply idealistic and utterly resolute, particularly in his quest to enthrone a theocratic government here in Nigeria, and in line with what obtains in the Republic of Iran. No doubt he was deeply influenced by the activities of the late Imam Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini who was the architect of the Iranian Revolution as well as the first leader (rahbar) of the Islamic Republic established in 1979. Imam Ayatollah had articulated the concept of velāyat-e faqīh (“guardianship of the jurist”) using a historical basis which underlay Iran’s Islamic Republic.

Chapter Three ushers us into another precursor to the emergence of the Movement which was the Funtua Declaration. Consequent upon Shaikh’s visit to Iran in 1980, he felt it expedient to share his experiences with an increasingly receptive audience at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. As related by the author on pg 26: “Later in April 1980, it was time for the usual Islamic vacation course. It took place in a northern city called Funtua. And it was there during his speech as the Vice President of the Muslim Student society that he gave a strong and historical speech which was from then on known as the FUNTUA DECLARATION.”

The author further elaborates: “This was the birth of the Islamic Movement in Nigeria. because even though preliminaries leading to the Islamic Movement started years before this, it only became a distinct and independent movement after the Funtua Declaration. In fact, out of fear of reprisals, the MSS released a statement disowning the Shaikh.”

This last paragraph is instructive in that it relates significantly to the future travails of the movement. After the declaration which led to the birth of the Islamic Movement in Nigeria, Shaikh and indeed the entire movement of which he was the leader began to experience antagonism from not just within Nigeria but from even worldly powers like America. But Shaikh was not to be deterred, as he kept on pushing forward his message of ‘Islam Only’ which was encapsulated in an eleven-point manifesto (outlined on pg 36). He did this majorly through increased Islamic lectures, evangelism, leafleteering and open demonstrations.

Chapter Four in brief reiterates the opposition that began to attend the activities of the Movement and its leader Shaikh El Zakzaky. Most significant was an incidence at the Federal Government College, Sokoto, which led to his arrest, trial and conviction; even though he felt he was unjustly convicted. However, Shaikh viewed the incarceration as a blessing in disguise, as it offered him a period for greater devotion to the worship of Allah.

In Chapter Five, the author stresses on the steady pace of persecution and periodic imprisonment of Shaikh, his family and followers by successive regimes, starting with the military regime headed by General Olusegun Obasanjo, right down to that of late General Sanni Abacha.

She relates a particular episode of the brutalization of Shaikh by agents of the authority and in narrating this, the depth of her love for her husband is made manifest (as related on pg 41): ‘One of them slapped me on my face and blood gushed out of my nose and my mouth. The most painful thing, I will always remember with great pain is their punching the Shaikh on his eyes again and again until his eyes became red and bloody. They also punched him in the stomach and because I was holding Muhammad in my arms, I could not protect him! I only shouted; Allahu Akhbar! Allahu Akhbar! Whenever I remember that, I felt great pain in my heart and tears ran down my eyes. I wish I was not holding my child in my arms, so that I could shield my husband with my own body.”

The author also relates that the spate of persecution of Shaikh hit a crescendo during the regime of late General Abacha but also ironically won him greater popularity among the masses, and this was in spite of seditious charges brought against him. She averred that in spite of this persistent persecution, and to the chagrin of the authorities prevailing over Nigeria, Shaikh’s popularity began to soar even higher: “Actually the persecution of the Shaikh along with brothers and sisters during the reign of Abacha increased the popularity of the movement and increased the support of our people for the struggle (pg 45).”

In Chapter Six, Trials and Tribulations, the author recounts Shaikh’s struggles, both within his ranks (some sectarian tussles and operational hijacks believed to have been orchestrated by the government in order to break the ranks within the Movement) and from outside of it; upon release from incarceration, he fought hard against those who stood as inhibitors to the spread of his newly introduced ideology which apparently did not resonate with a vast cross-section of the largely dominant Sunni-inclined population.

But what do you call an anti-western democratic ideologues which bears the explicit goal of changing the system of government in place? If the man is Sheikh Ibrahim Yaqoub Zakzaky, you call him a revolutionary – Islamic revolutionary? The authorities rather perceived him as a prime mover in the transformation of many youths to rebellious lot against the authorities of the Nigerian Federation, in little more than half a century; the Zaria-born Sheikh Ibrahim Yaqoub Zakzaky sought to overturn the current governance system by radicalizing a group within the Muslim ummah through public addresses, lectures, and conferences.

As earlier stated in this review, his famous lecture at Funtua in April, 1980, now popularly referred to as Funtua Declaration, kick started his activism in this direction; it was the turning point or point of divergence from the mainstream doctrine that propelled the largely Sunni population. In Chapter Seven, the author elucidates on one of the divergent areas which has to do with the elevation of Aisha Rasulullah’s wife above Lady Fatima, his daughter (May Allah be pleased with them all). The Ja’afari’s school of thought, of which they became proponents of, sought to change an age-long narrative to henceforth favour Fatima, her husband and their offspring. In this, the movement drew inspiration from fragmented information premised on evidence from research into historical documents they were opportune to lay their hands on. As such, they began to spread the message with greater zeal, drawing much-needed courage and strength from the provisions of Glorious Quran – SUratul Kahf vs 13 -14. One particular event that became elevated within the movement was Lady Fatima Day!

In Chapter Eight, the author enlightens us on the core programmes and activities of the organization, starting with the description and activities of the various organs of the Movement. These organs include those saddled with education/proselytism, health, security and event planning amongst others. At the top of the movement was the titular head, Shaikh Zakzaky, assisted by various units and sectional coordinators (the coordinators presided over various communities but would often defer to the headquarters in Zaria in virtually all matters).

In Chapter Nine, the author advances reasons that led to the annual Quds’ day celebrations which began in 1984: an event which holds in the form of supposedly peaceful street demonstrations, to support the cause of the Palestinians, usually taking place during the last Friday of every Rammadan. That of 2014 was perhaps one of the saddest points in the history of the Movement as the author lost three kids to the brutality of law enforcement agents! She equally blames the group’s misfortune on the avowed enemy of the worldwide Shia movement, America, as well as its agents in the Middle East – Israel!

In chapters 10 to 12, “Zaria Massacre, 2015” and “Personal Account of Zaria Massacre, 2015”, the author gives a detailed account of the horrid massacre of members of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria in 2015 by government agents; she particularly recounts her bitter experience and the loss of three kids in one day. Altogether, this brings to six, the number of their biological kids killed by agents of the Nigerian State!

The breakup of their annual Unity Week celebrations during the First of Rabiul Awwal, the siege and eventual destruction of the Movement’s headquarters which also serves as Shaikh’s homestead, and the physical brutalization of Shaikh are all extensively discussed within the final three chapters of the book.

In the last chapter, “The Aborted Trip to India for Medical Treatment,” the author details their experiences with a failed attempt to seek medical attention in an India, particularly due to the treachery of both the Nigerian and Indian governments in the matter. In the endnote, she expresses her bitterness towards those who have held the reins of governance sine the emergence of the Movement in Nigeria but ends her narratives in the book thus: she still venerated and offered prayers for Prophet Muhammad (saw) and his ‘pure progeny’ (ostensibly referring to Fatima, her husband and her offspring).

Conclusion

Personally, I stridently condemned the steps the army and various state machineries took in relation to the Movement, and of course the report of the Kaduna State government’s own inquiry vindicates this position. But then many persons still supported the expediency of the army’s conduct based on drawn-out perceptions of a group that has arrogated powers to itself, to the detriment of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

I have always believed in the inalienable right of every man to hold on to his belief and I have thus refrained from taking any side on the incontrovertibility or otherwise of the differing views of the various Islamic sects with regards to certain histories and of course, aspects of the Islamic religion. What has always been clear to me is the often-quoted surah of the Quran Chapter 2 vs 256: “There shall be no compulsion in [acceptance of] the religion. The right course has become clear from the wrong. So, whoever disbelieves in Taghut and believes in Allah has grasped the most trustworthy handhold with no break in it. And Allah is Hearing and Knowing.” This verse has buoyed my thinking in this direction.

However, in Chapter 4 vs 5, it is said: “O ye who believe! Obey Allah, and obey the Messenger, and those charged with authority among you. If ye differ in anything among yourselves, refer it to Allah and His Messenger, if ye do believe in Allah and the Last Day: That is best, and most suitable for final determination.” However, this second verse might be interpreted according to the whims and caprices of the reader.

In 1986, I was in the School of Basic Studies, Zaria, when I was opportune to stumble on an ongoing sermon by a man whom I learnt to be El Zakzaky, leader of an Islamic sect; then, despite my being quite young, yet, rightly or wrongly, I had the notion that his sermon was inflammatory and so, when I began to notice the way and manner the leader and the adherents of Shiites began to operate in Nigeria, I knew in my mind that their activities would one day snowball into an inevitable crisis between them and the state. And this eventually happened! Albeit, I thought the Army could have rather harnessed the potentials of Shiites in helping to deal with the menace of such unorthodox groups like the Boko Haram, given their much more refined organizational methods – or that much more constructive engagement could have sufficed rather than the brutal use of unbridled force!

The words in this heart-wrenching book are a call for justice in all forms. Like Thrity Umrigar said in her book, Honor: “Human beings could apparently be turned into killers as effortlessly as turning a key. All one had to do was use a few buzzwords: God, Country, Religion and Honour. The most dangerous animal in this world is a man with wounded pride.” But then I will summarize my personal position against the use of unbridled force by any civilized State employing the words of the notable writer and philosopher Edmund Burke: “The use of force alone is but temporary. It may subdue for a moment; but it does not remove the necessity of subduing again; and a nation is not governed, which is perpetually to be conquered.”

Appendix

Ref. Premium Times Nigeria

https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/477003-timeline-ibrahim-el-zakzakys-long-road-to-freedom.html

TIMELINE

December 12, 2015: Nigerian Army attacked IMN members who had blocked a public road, killing many of the Shiites.

December 13, 2015: The IMN released a statement saying that Mr El-Zakzaky’s son and wife were among the hundreds of Shiites killed.

December 13, 2015: The IMN insisted that its members did not attack the convoy of the Chief of Army staff, as alleged by the Nigerian Army.

December 14, 2015: The army continued the attacks on the Shiites, particularly at the IMN headquarters in Zaria.

December 15, 2015: The army said the Shi’ite leader, Ibrahim El-Zakzaky, and his wife were “safe and in protective custody.”

December 18, 2015: President Buhari did not make any public statement on the killings but a presidential spokesperson said that the incident was “a military affair.”

December 23, 2015: Human Rights Watch published a report saying over 300 members of the Shiite group were killed.

January 14, 2016: The Islamic Movement released a statement saying its leader, Mr El-Zakzaky, and his wife, Zeenah, were recuperating from gunshot wounds at an undisclosed location in Abuja.

April 5, 2016: Human rights lawyer and counsel to Mr El-Zakzaky, Femi Falana, revealed that Mr El-Zakzaky had become partially blind.

December 2, 2016: A high court ordered the release of El-Zakzaky noting the decision of the government to hold him for so long was dangerous.

Citing the death of former Boko Haram leader, Mohammed Yusuf, in custody, the judge said: “If the applicant dies in custody, which I do not pray for, it could result in many needless deaths.”

The judge ruled that the government should within 45 days release the applicant and his family to the police, who shall within 24 hours take them, guarded by escort, to a safe place.

December 14, 2016: A human rights group described the continued detention of Mr El-Zakzaky despite the court ruling as “a hardening of dictatorship behaviour.”

January 15, 2017: The 45 days deadline given by the judge elapsed with the Nigerian government failing to release the IMN leader.

January 16, 2017: Amnesty International told the Nigerian government to obey the court and release Mr El-Zakzaky and his wife.

March 9, 2017: The wife of Mr El-Zakzaky, Zeenat, wrote an open letter to President Buhari recalling the events of July 2014, “the month that the Nigerian army under former president Goodluck Jonathan extra-judiciously killed three of my sons among 35 Muslims exercising their constitutional rights of assembly.”

May 23, 2017: The Federal Government said Mr El-Zakzaky was still in detention because there are additional charges against him for which he has not been granted bail.

May 24, 2017: The Presidency declared that Mr El-Zakzaky’s detention was in the public interest.

November 9, 2017: IMN made a fresh demand for his release on health grounds.

January 13, 2018: The IMN leader made his first public appearance more than two years after he was detained by the Nigerian government.

April 18, 2018: The Kaduna State Government filed an eight-count charge of homicide against Mr El-Zakzaky and his wife over the death of a soldier in the December 2015 incident.

June 21, 2018: The absence of a judge stalled the trial of Mr El-Zakzaky at a Kaduna high court.

October 29, 2018: Clashes erupted between security forces and IMN followers in Abuja.

November 7, 2018: The Kaduna court rejected the bail application filed by the Shiite leader and his wife.

November 8, 2018: Nigeria’s Information minister, Lai Mohammed, in a leaked video, claimed that the government spends about N3.5 million monthly to feed Mr El-Zakzaky.

August 5, 2019: The Kaduna State High Court granted the Shiite leader and his wife leave to travel to India for medical treatment.

August 5, 2021: Nigeria’s secret police, the SSS, pledged to obey the court order granting Mr El-Zakzaky bail.

August 13, 2019: Mr El-Zakzaky arrived in India for medical treatment.

August 14, 2019: Mr El-Zakzaky alleged that the condition at the Indian hospital he was taken to was worse than where he was detained in Nigeria.

August 16, 2019: He was returned to Nigeria and he alleged that the federal government working with the Indian government frustrated him from getting adequate treatment. Upon his return, he was placed under arrest.

August 28, 2019: The Nigerian government accused Mr El-Zakzaky of being sponsored by Iran to replicate the 1979 Iranian revolution in Nigeria.

February 6, 2020: The court granted Mr El-Zakzaky and his wife access to personal physicians.

February 6, 2020: The court fixed February 24 and 25 for the continuation of his trial.

February 24, 2020: The court ordered prison authorities to allow the couple full access to medical services before taking their plea on April 23.

November 19, 2020: The court adjourned Mr El-Zakzaky’s trial to January 25 and 26 for further hearing.

January 23, 2021: Authorities of the Nigerian correctional facility in Kaduna State said they were not aware that the IMN leader and his wife tested positive for COVID-19 as rumoured.

January 26, 2021: The trial of Mr El-Zakzaky, and his wife, Zeenat, was adjourned to March 8 and 9, 2021, for further hearing.

March 8, 2021: The court adjourned to March 31 for the continuation of trial. Justice Gideon Kurada adjourned the case to allow the prosecution to close its case.

March 31, 2021: Prosecution closed its case, and asked the court to sentence Mr El-Zakzaky. The judge adjourned the case till May 25, 2021.

July 1, 2021: Kaduna State High court set aside July 28 to rule on the no-case submission filed by the couple.

July 28, 2021: Court frees the couple in a ruling that lasted over eight hours. The judge upheld the no-case submission filed by Mr El-Zakzaky and his wife.

July 28, 2021: The Shiite group said the judgment of the Kaduna State high court has vindicated its members and is a victory for them.

July 29, 2021: The Kaduna government said it would appeal the ruling, an indication that the cleric and his wife are not yet totally free.

* Dr Usman Oladipo Akanbi, a senior lecturer at the University of Ilorin, is the National President, Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA)