Today is a great day for me to stand in front of the great minds of the Nigerian literati and dialogue about the great fortune I had in the last quarter of the 20th Century and the first quarter of the 21st Century, to tell my stories in plays, poems, essays, articles, and novels to the global public.

But to move forward, I wish to enter a caveat. You invited me as your writer for July, but I do not consider myself a writer; I am just a simple storyteller. And please don’t get me wrong. I love and admire great prose, poetry, and the rich dialogues of plays. But then, I must clarify my mission in the arts in the 75 years of existence. Writers put words in structures that focus on crafting sentences and phrases, prioritising style, tone, and language, often at the expense of the story.

The world’s literary giants have enriched literature in different languages, and the world is better for it. These writers engage us by showing the beauty of language, expose us to exceptional writing styles and linguistic techniques, and enrich our lives in various ways. Being a storyteller is different. As a storyteller, my priority is the story, and I have often felt no qualms about sacrificing the style, tone, and beautiful words that fascinate the story. I am always deeply suspicious of writing in English, a foreign language with tantalising textures and word-smithery. I constantly sniff fakery.

My aim in literature is to craft narratives that have an emotional impact on my public: Nigerian and African people, the oppressed black people, and those suffering injustice but without a voice nor fist to raise in counter-attack self-defence.

I started my literary career as a storyteller from orature. In the beginning was the word, and then the rest was memory. I was born in three villages: Mkar, Kasar, and Gbagir. My father was a Dutch Reformed Church Missionary who undertook Church planting activities, constantly moving from one local community to another.

There was no electricity, no pipe-borne water, and no wells except large ponds on banks of rivers, which my father dug to start Christian village communes. My earliest memory is being carried to Morning Prayer and Church services, then to start the day by going to the farm. Much later in the night, unless it rained heavily, we listened to stories told by our parents and relatives.

Stories were told by firelight that warmed during the Harmattan season and by moonlight. This was my reality. The transistor radio my father owned was not for entertainment. It was religiously tuned to the BBC and later the national news. It was held exclusively in a special Tabernacle as a sacred relic of sophistication.

I was introduced to the Tiv “Kwagh-hir” and “Kwagh-lom” story-telling tradition at a very tender age. These popular narratives were humorously subversive of authority. The authority figures were almost always defeated, to the delight of the village audience, by Alom, the trickster.

I lived at Gbagir with my parents and siblings in a simple room with piles of literary works and comics from America. Every day, I accompanied my father to the classroom, but I was barred from entering because I was smallish, and only children whose right fingers could touch their left ear stretched across the top of their heads qualified and were enrolled as school pupils. I felt humiliated and discriminated against because of my size. And I realised the horror of being a minority. Too short for school!

I was otherised by the rigid regulations enforced by my father. So, I began a rebellion by hanging on to the open windows and practising reading and writing in the sand outside the classroom. After school, I challenged the majority daily with better comprehension stolen from across the border until I qualified to be a pupil the following year, 1956.

Our home received monthly supplies of comic books written in English. I do not know when I started reading and writing as a child, but I was fascinated with reading the Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy stories and adventures.

Then, amazingly, I came across the “Brer Rabbit,” “Brer Fox,” “Brer Bear,” and “Tar baby.” These books were not meant to be taught to school children because there was a law to teach us in the vernacular. I learned the alphabet and the names of trees, vegetation, and fruits in the Tiv language when I was six. I still write fluently in Tiv.

By the time I entered primary school, I had become a storyteller, I presume by contagion from the masters of words and memory. I do not know how I began to speak the English language, nor how these books and later other books of literature like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Genevieve by Elizabeth Steward, and the Tiv Bible translated as Akaa Bibilo, made a great impression on my upbringing. I read and read and refused to do chores and “handwork.”

I was punished in Primary School by compulsory fatigue and was constantly severely caned for being unable to be creative with my hands in handwork. I then discovered how to disappear altogether. By furtively climbing up a big mango tree to silently read for hours. In Primary School, I read “She,” “King Solomon’s Mines,” and “Alan Quatermain” by Rider Haggard.

But before I completed Primary School in 1963, I was fascinated by the novel “Veronica, My Daughter.” The play, “Trial of Patrice Lumumba and his Execution” by Ogali A. Ogali, transfixed me. These were Nigerian writers!

In Secondary School, I read a wide variety of American Literature. Bristow was an American-run Missionary school in Gboko. Still, in my final year, I was examined in Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and “As You Like It,” as well as George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice.”

But I went on a rampage, reading everything there was to read in our fully stocked library. I thoroughly enjoyed Mark Twain’s “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn” and all the novels by Richmal Crompton, the “Just William” series. It was then that I had an intense beckoning to write my stories.

I started writing plays when I was in Secondary School. I don’t remember the titles, but they were all about the legendary American cowboy icon I pulled out from comic book strips, Roy Rogers. In the Drama Club, we acted in “Julius Caesar” and “As You Like It.” We found it more exciting to write our plays on the side, on American Cowboy themes, foolishly identifying with the cowboys against their Indian victims.

Bristow Secondary School was a pivotal site for self-discovery, where I navigated primeval experiences that informed my burgeoning identity and set me on the path to becoming my authentic self.

My Process

In all my writings, I have tried to be the conscience of my society, my beloved country of birth, Nigeria. I have been engaged trenchantly with the moral issues of my time. Over the years, these ethical issues have been distilled in my writings to help me achieve clarity and communicate my views to speak truthfully about the problems as I understand them.

My biggest motivation has been to tell stories about human follies, extremities, and aberrations rooted in leadership failure and injustice. Through writing, I strive to achieve clarity of thought, question prevailing narratives, and subvert the harmful social norms perpetuating inequality and injustice.

As a storyteller, I am participating in a human conversation that started several millennia before my birth and before I found a voice to enter the conversation. My entry point is where I make the most of it: seeking clarity and voicing dissent where I see injustice and leadership collapse.

Writers and storytellers are carriers of cultural artifacts. We are the conscience of our societies. My role is to illuminate. The Nigerian writer has no greater responsibility than to engage in nation-building.

I have stood against public corruption in my public and private life and have condemned Africa’s rapacious and corrupt elite. The African elite has become the new conquerors of our people, who are reeling under oppression in various disguises. The writer must speak truth to power by telling stories of unique power and sufficient complexity that can engender change through collective effort.

I write to help shift perspective and urge social action. I hope to raise consciousness through enlightenment. Our democracy has devolved into a parody and travesty, where the elite have engineered a new political system antithetical to true Republican democracy. This Ogacracy—a government of the powerful, for the powerful, by the powerful—allocates influence proportionally to wealth and the ability to wield it ruthlessly. The result is a toxic brew of inequality, cronyism, favoritism, and booty capitalism, perpetuating a system of injustice and entrenching the power of the few.

In America, like Nigeria, democracy is threatened not so much by leadership failure but by the propensity of the followers (voters) who choose social goals like personal aggrandisement, self-promotion, ethnic and racist jingoism, illicit, unfair, and unequal allocation of resources, opportunities, and access to more easy money. The followers share the blame that the politicians (leaders) are becoming investors in these social goals and losing sight of concrete investments in health, education, and agriculture.

My Style

My story-telling style is characterised by a distinctive, fragmented narrative structure comprising loosely connected chapters, episodes, scenes, strands, and happenings that are self-contained and interconnected. Each element stands alone, yet seamlessly dovetails into the next, creating a rich tapestry of organically unfolding experiences.

My writing is a deliberate affront to complacency, a challenge to the status quo, and a beacon for the discontented. I seek to disturb, outrage, and galvanise, pushing readers and audiences of my plays to confront stark truths we often ignore or rationalise—the injustices that demand our attention, actions, and collective outrage.

The heroes of my plays, poems, and novels are ordinary people, the “Agboros”, rather than the “Ogas.”

I am worried and continuously ask myself if we, the writers, have used the pen as a double-edged sword to craft compelling stories to cut through the thick fog of ethnic racism, pervasive greed, and grave injustices that are rampant and the recolonisation of our people by the rapacious political elite, traditional rulers, and the business-political-military complex.

I believe that writers can hold the pen as a double-edged sword to inspire a new great African generation to nation-building imperatives by cutting both ways against ethnic bigotry and the theft of a meaningful future from the youth who are left in despair and are now poised to express dissent in anti-elite insurgencies. We need to weld artistic words into weapons to confront injustice anywhere it rears its head by confronting the oppressors and helping the victims to heal.

The pen the writer wields is to instigate a moral revolution in which we can all create history together as heroes in rebuilding our country rather than helpless victims of apathy, greed, and hostility. I see my responsibility to brandish my pen as a double-edged sword: to raise consciousness from ordinary conformism and helplessness to empower and energise the revelation of new perspectives.

The writer is the doubled-edged swordsman and woman like Roman’s Ancient Legion armies, the Japanese Samurai, the Mongolian Hordes, and the Aztec Warriors, who defeated their enemies in decisive battles.

Let us also rise to our call of duty armed with stories, poems, and plays like the Spanish playwright and novelist Frederico Garcia Lorca, who was described by the Spanish soldier who shot him dead as having “done more harm with his pen than others have done with their pistols,” or Pablo Neruda whose poems are cited by youth revolutionaries today from Chile to Egypt.

One aspect of my literary style has been my blunt refusal to glorify the distant past histories of our ancestors and their brutal conquests and injustices, as well as the steeping of consciousness in metaphysical calabashes and pots of magical realities. I believe these writers who engage in these forms of glorification of transgressive and gory metaphysical experiences in the name of “art as the mirror of society” are doing grave injustice to Africa; they are spreading a false consciousness and belief in spirit beings which are merely hostile capricious forces that deny Africa entry to modernity, and pull us back into apathy, fear, and victimhood.

These Juju priests must be swept aside to give rise to a new nationalist spirit of scientific critical thought and the embrace of change. Africa desperately needs new visions by the new nationalist writer who has delinked from tribal moorings and spiritual hallucinations.

The Nigerian youth are impatient in finding out who they are. They look vainly at the Juju priest writers and ethnic champions for their new identities. They have now mollified their expectations and look up to Nollywood and Big Brother Naija to define them. It is time for the writer and storyteller to demand an immediate stoppage of the miseducation and misinformation of the misguided youth to foster the next great generation.

I have tried to present a nationalist literary ethos in all my writing, promoting and presenting unity in diversity. Everywhere I have traveled in this country, I have found the ordinary Fulani, Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, Idoma, Igedde, Tiv, and Jukun living together as victims of the elite who have spread their deadly viruses of ethnic racism, religious and ethnic bigotry, ethnic wars, banditry, greed and separatist agitations that drive Nigeria asunder.

I am 75 years old now, and I am worried that death or disability might scuttle the novels, plays, and poems I have lined up in my brain to give hope for a better world where those who lead would harness the globe with greater responsibility and those who live in the basement of the world can also raise their heads to behold a new dawn filled with love, compassion, and goodwill.

Through dialogues like this, our candle might flicker and quench into new candles of light and conscience to brighten leadership responsibility and hope. I welcome you to the dialogue. Thank you.

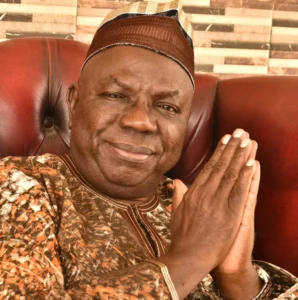

* Professor Iyorwuese Hagher, a former Nigerian university tutor, High Commissioner to Canada, and Cabinet Minister, is a United States-based independent public intellectual, playwright, novelist, poet, and essayist