It was raining when I drove into Kano on that sultry day in June. All through the six-hour journey from Abuja, the weather had remained bright and clear except for a mild shower in Zaria and later at Dokomaya, a dusty roadside hovel some distance to Kano.

Then, suddenly, as I approached Kura, a few kilometres into the ancient and historic city, the heavens opened up. With the rain, the usually congested Kano traffic was now clear of the ubiquitous motorbike riders popularly known in the city as ‘yan acaba’.

The hot weather, which had thrown the city into an unprecedented heat wave the previous week, had remarkably gone down.

Expectedly, the rain also prevented the usually boisterous almajirai from ploughing their begging trade on the streets. Instead, I could see them on a roadside clearing playing soccer, their begging bowls littering the margins of the makeshift football field like miniature spectators. And, as I observed their frail, supple limbs dance over a football in movements that would have made Austin Okocha green with envy, I thought to call the attention of the Green Eagles coach, Shuaibu Amodu, in case he needed fresh feet for his already aging team.

I had come to Kano in my position as the President, Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), on the invitation of the organising committee of the launch of Alhaji Bashir Othman Tofa’s eight books, all written in Hausa.

While Tofa’s reputation as a former presidential candidate of the defunct National Republic Convention (NRC) and a successful Kano businessman were well established, his position as an author was not that well defined. Rumours even had it that the book launch was actually a prelude for the politician-cum-writer to re-launch his political career.

As if to support this claim, the vicinity of the Sani Abacha Stadium venue of the event was in a carnival mood, with drummers, praise singers, party faithful and pickpockets having their day. The praise singers were so ebullient that they could even be seen assisting some politicians to fold their flowing manyan riguna (babbar riga) while at the same time heaping praises on them. “You will soon become Nigeria’s President, while your wife will become a senator,” one praise singer could be heard serenading an obviously impressed politician.

The indoor sports hall of the stadium was packed with politicians of all cadres, traditional rulers and all forms of uniformed security agents – the police, soldiers, officials of the Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC), Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC), and the green uniformed state security outfit, Hisbah. The Hisbah was originally conceived to arrest violators of the Shari’ah law.

Apart from guarding the dignitaries at the occasion, the security personnel were also detailed to protect the trunks of money expected to be made from the book launch.

Tofa explained that he decided to write in Hausa because of his strong belief that using the English language to teach has a negative consequence on the learning process

I was later introduced to the author who appeared very relaxed and full of smiles in spite of the pressures of the big event.

In a brief interaction, Alhaji Tofa explained that he decided to write in Hausa because of his strong belief that using the English language to teach has a negative consequence on the learning process. It was his assertion that local languages be encouraged in schools as children easily get more knowledge in their native languages.

The roll call of dignitaries at the event was quite impressive. Apart from the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, whose arrival was announced with booming gun shots, Governor Ibrahim Shekarau, Alhaji Yusuf Maitama Sule, Professor Shehu Galadanci, the representatives of the governors of Edo and Katsina states, federal, state and local government legislators, among others, were at the well organised and colourful ceremony.

More importantly, I was quite impressed with the prompt arrival of the VIPs. The whole event did not take more than the scheduled two-hour duration.

With Tofa’s eight books: Tunaninka Kamanninka (The Way You Think Reflects in Your Character), Kimiyyar Sararin Samaniya (Space Science), Kimiyya da Al’ajaban Al-Kur’ani (The Science and Wonders of the Qur’an), Gajerun Labarai (Short Stories), Amazadan a Birnin Aljanu (Amazadan in the Land of the Spirits), Amazadan da Zoben Farsiyas (Amazadan and Farsiya’s Ring), Rayuwa Bayan Mutuwa (Life After Death), and Mu Sha Dariya (Let Us Laugh), Hausa literature has garnered a very wide acceptance across the society.

As good as this development sounded, there still remained for the African, nay the Nigerian writer, the urgent need to answer that nagging question of “the language issue.” While the idea of writing solely in one’s native language seemed patriotic, the problem was getting the critical mass of readers to make the exercise worth while. In 1986, after the Kenyan writer, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o declared that he would henceforth only write in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, he was forced to revert to the English language when he could not garner the expected reading audience he wanted.

The failure of Ngugi to have a sizeable readership in his native language was similar to the experience of many African writers who tried to write in their indigenous languages.

Another writer who had raised the issue of ethnic literature was Obi Wali who, as far back as 1963, had claimed that Africans who wrote in European languages were wasting their time and talent since, according to him, African literature could only be written in indigenous African languages.

However, not every African writer is against the use of English as a medium of communication. One of these was the world renowned writer, Chinua Achebe who, years ago, observed that “the real question is not whether Africans could write in English but whether they ought to. Is it right that a man should abandon his mother tongue for someone else’s? It looks like a dreadful betrayal and produces a guilty feeling. But for me, there is no other choice. I have been given this language and I intend to use it. I hope that there always will be other writers who will choose to write in their native tongues and ensure that our ethnic literature will flourish side-by-side with the national ones.”

As I later leafed through Tofa’s well produced and well packaged eight books, I hurt badly because I could not read what the reviewer had promised to be very engaging and interesting books since I did not understand Hausa.

Here was the dilemma. How did we ensure that our brothers and sisters of other ethnic persuasions appreciate our stories if we only write in our native tongue?

This was why to me, bilingualism, rather than isolated indigenous writing, remained the way forward for African Literature.

Just as Achebe had suggested, we had to allow our ethnic literature flourish side-by- side with writing in European languages so we could all enjoy the beauty of our literature.

Alhaji Tofa had to be commended for producing such beautiful Hausa books, particularly against his background as a politician and businessman. Apart from the over ₦50 million collected at the event, the release of Tofa’s eight books was a worthy addition to the very active and prosperous Hausa Literature culture.

By the time I took my leave of the Sani Abacha Stadium, the rain had stopped and the ’yan acaba and the almajirai were back on the streets. So also were the myriads of beggars who, in mournful voices and pitiable appearances, swarmed on vehicles.

At the ever busy Kofar Nassarawa roundabout, an unappreciative beggar was angry that I gave him only ₦50 and he kept demanding for ₦200 or nothing else. A few metres later I witnessed a violent sandstorm that blew everything in its wake, enveloping the approaching twilight in a blanket of dust, water sachets, cellophane, etc.

Unfamiliar with the ever busy Kano roads, I missed a turn and came upon the abandoned railway station terminus, a beautiful colonial tribute to a sadly forgotten major form of transport and commerce.

In my writer’s mind, I could imagine the scene in the station many years ago when our railway system was still active; weary travellers departing from the wagons to the warm embrace of their friends and relatives while hawkers called out their different wares in melodious voices.

All that was gone, what was left of that glorious and busy era were dilapidated railway wagons, empty offices and rotting signboards.

It was soon time for me to depart Kano, a city that never failed to captivate me with its ancient and modern charms.

Very reluctantly, with the sonorous voice of Aminu Ladan Abubakar, a.k.a. Ala (a poet and member of ANA Kano), on the Freedom Radio singing his favourite song “Bakan Dabo” (Praise to the Emir), I gunned down the accelerator and nosed my car towards Abuja.

(This is Chapter Twelve of my travel stories collection: TALES OF A TROUBADOUR (Literamed Publishers 2019).

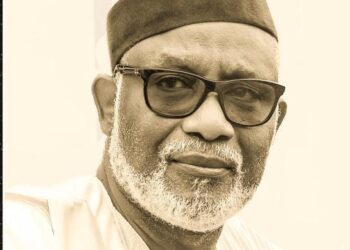

Dr. Okediran is the President of the Accra-based Pan African Writers Association (PAWA)