There was a cleansing whiteness and quietness to the house, a kind of purity that forced one into the now. A pot of incense was frequently burning in the room, its sweet smell building on the lack of pace and urgency, a permission to live in the now Hermit’s Paradise.

It was late in September when I moved into the Hermit’s Paradise. It was the most effortless experience. The room I was staying in had a limited view of the side of the house, but a breathtaking view of the sunset. I always returned in time to see the sun sink into another side of Kaduna and leave behind a trail of orange. As the only occupant, I had a lot of privacy that left a lot of room for personality.

My day was usually brought to life by my 5:20 a.m. Subh alarm. After prayers, I take another round of sleep that ends at 9:00 a.m. Sometimes, when my companion, Bello, needs to get to the office early, this timing usually left me rushing through a very brief bath and chewing the rest of my breakfast in the car. More frequently, however, it gave me enough time to have thoughts in the shower and an equally slow breakfast.

Prime and Bell is four tracks on the radio away from the house. Like the house, the office had that immaculate whiteness to it. It had an open plan with partition panels that separated the employees from The Partners. One of the offices was that of the founding partners, Baba Abba, whose place is the Hermit’s Paradise, where I stayed. In the mornings, there was always the scent of coffee coming from his office, snaring its way into the nostrils and lingering there like a promise. It is sometimes complimented by the scent of snacks bought for the employees or prepared from home. The other office is that of Baba Dahiru.

I

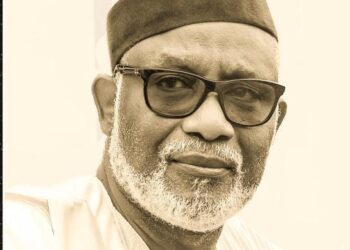

I spent a lot of time learning administrative work under Baba Abba. There was a quality in Baba that was missing in most of the adults I knew. He was a listener. He would face you squarely while he teaches or talks to you, like that was the most important job of the moment. No second felt like an intrusion. Instead, it was always an opportunity to lean back and learn from his insightful discussions and lessons.

II

A florist we once went to with the eldest, Aisha, gifted me a plant that now resides in a brown pot on the verandah of the Hermit’s Paradise. Sunset Bells. From a distance, you could not tell the brown pot from all the others, but a closer step revealed a different pot with a different wilting plan that has resisted all attempts to make her bloom. A camouflaging misfit. It is a metaphor for my first hours at the Hermit’s Paradise. That, however, was very quick to change. Even though I never quite made it out of my cave, the family was quick to make me feel at home. Their hospitality was a different kind of watering, the kind that could make even the most reluctant Sunset Bells bloom early.

There was an easiness to Mama and Baba’s companionship, something about every moment that made every second picture worthy… Their kindness reflected in the atmosphere in the house. There were no raised voices, no displays of temper

III

’Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.’

A constant sight in the main living room was an enduring love that had been decades in the nurturing. There was an easiness to Mama and Baba’s companionship, something about every moment that made every second picture worthy. Usually, they would be watching football or some other television show, making light commentary and conversation. You could smell the delicate kindness in the air whenever they were in each other’s presence. Their kindness reflected in the atmosphere in the house. There were no raised voices, no displays of temper.

IV

It is a chilly December morning, my last at the Hermit’s Paradise. I can almost hear my heartstrings snapping. I am standing outside the house. Rabi’atu is telling her kitten to say goodbye to me. I hold her for a few seconds. “I am no more scared of kittens,” I say as I hand her back. She is small and ginger and beautiful and always lurking around the door to the house.

Heartstring snaps. I am back in the house for my other bags. Aisha is out to say goodbye to me. She is telling me to tell the driver to stay for lunch. I tell her we are very late.

Heartstring snaps. We are outside the house again. Aisha has packed a meal in a takeaway for the driver. We say goodbye.

Heartstring snaps. There is a lump in my throat that I cannot swallow away. The driver is telling me something about some event my father should have attended at some venue we passed. I murmur in reply. My mind is somewhere back in the house, gliding like a ghost, feeling the white walls again, inhaling the burning incense. There is a desperation to remember every detail of the experience, from the dials of the red car we drove to work in down to the sight of the teacups sitting on coasters on the dining table every morning. A desperation to always remember the love and the kindness and pour it over the rest of my life like confetti. But more than the desperation, there is a gratefulness for the experience, the acceptance that even if the details were to all fall through the quicksand of my memories, there would always be the impression that it was all love, even when I am not able to remember what it looked like.

* Hadiya A. Tilde lives in Bauchi