Nearly one-third of patients with stroke of unknown cause have heart rhythm disorder that can be treated to prevent another stroke, says a Nordic Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke study.

The study, presented at the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) 2022 Scientific Congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), was posted on ESC website on Monday.

The News Agency of Nigeria (NAN) reports that the EHRA congress is underway from April 3 to April 5 at the Bella Centre in Copenhagen, Denmark and online.

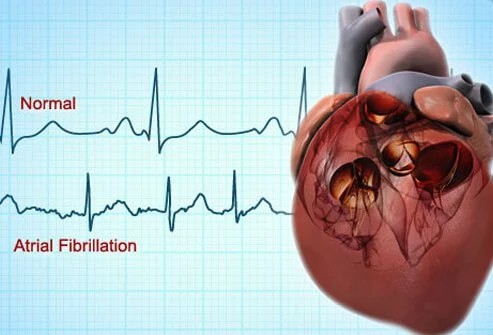

The Nordic Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke (NOR-FIB) study examined the ability of continuous heart rhythm monitoring for one year with an implanted device to identify atrial fibrillation in patients with an ischaemic stroke or mini-stroke (transient ischaemic attack; TIA) of unknown aetiology.

The study author, Dr Barbara Ratajczak-Tretel of Østfold Hospital Trust, Sarpsborg, Norway, said that more than 90 per cent of stroke patients found to have atrial fibrillation had no symptoms of the heart rhythm disorder.

“For many patients, atrial fibrillation would have gone undiagnosed and untreated without continuous monitoring, putting them at risk of another stroke,” she said.

Ratajczak-Tretel said that most strokes are ischaemic, meaning a blockage stops blood flow to the brain.

According to her, the cause of one in four ischaemic strokes is undetermined.

“The best therapy to prevent another stroke depends on the underlying cause.

“Those with atrial fibrillation should receive oral anticoagulants but a definitive diagnosis is needed before these drugs can be prescribed. Atrial fibrillation can be transient and asymptomatic making it difficult to detect,” she said.

She said that the observational study included 259 patients with no documented history of atrial fibrillation from 18 centres in Norway, Denmark and Sweden.

According to her, all patients received a cardiac monitor, which was implanted a median of nine days after the stroke or TIA.

She said the device was one-third the size of a AAA battery and was inserted subcutaneously over the heart under local anaesthesia.

Ratajczak-Tretel noted that data from the device were transmitted automatically through a secure network to a core lab of two neurologists and two cardiologists and evaluated once a week.

“When atrial fibrillation lasting at least two minutes was detected, the core lab contacted the patient’s physician who then prescribed oral anticoagulants. Patients were followed up for 12 months,” she said.

She said that during the 12-month monitoring period, 74 patients were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, of whom 93 per cent were asymptomatic.

Ratajczak-Tretel said that oral anticoagulation was recommended for all patients with atrial fibrillation and at 12 months, 72 of 74 patients were on this therapy.

She said that during follow-up, two strokes occurred in the atrial fibrillation group (both before the first atrial fibrillation episode was detected and anticoagulation initiated).

According to her, nine occured in patients without atrial fibrillation, noting that the difference is not statistically significant.

“In this study, we found that an implantable cardiac monitor was effective for diagnosing underlying atrial fibrillation, which was identified in 29 per cent of patients with a stroke or TIA of indeterminate cause.

“As the probable cause of the stroke or TIA was detected, these patients were able to start oral anticoagulation.

“Atrial fibrillation was asymptomatic in most cases and may not have been detected or treated without continuous monitoring,” she said. (NAN)