No less a production characteristic than the typologies of Hausa video film was the marketing of the films which further illustrated its market-driven nature. When Tumbin Giwa Film Productions in Kano edited Turmin Danya in 1990 they faced the problem of marketing it.

The production of the video film did not come with an embedded film marketing strategy that would be cost-effective to the drama group, considering in fact the financial hurdles they had to overcome to produce just one video film. Further, the cassette dealers in Kano, dominated by Nigeriène Hausa immigrants, had no interest in marketing a Hausa video film over the Hindi, American and Chinese films they were making a bustling trade out of pirating. A Hausa video film was an anomaly because the main television stations of NTA Kano and CTV Kano, as well as NTA Kaduna, had popular dramas that were easily available via unofficial channels. Further, it would not be as easily pirated as overseas films because the owners were local and could control the production and distribution. On the face of the popularity of TV dramas and their ready availability, it did not seem to make marketing sense to accept Turmin Danya. They therefore refused to market it.

The Tumbin Giwa drama group also faced a second problem of getting enough blank tapes to make multiple copies of the video—and again the marketers, who were the main distributors of the tapes, refused to co-operate as they did not wish to reveal their sources. Generally, they were not particularly keen on the development of the indigenous video film industry because it was a loose cannon in their lucrative pirating.

Most of the marketers lacked modern education and sophistication to market a film within the conventional process of film marketing. This was more so because creating and implementing advertising and promotional efforts designed to make a film stand out in a competitive market environment, film marketing typically used the same methods other products dif—and these required a corporate mindset which the typical Hausa market square merchant simply did not have. They therefore rejected Turmin Danya. However, they did accept to distribute it if the producers would find enough tapes to duplicate it themselves and bring it to them “ready-made”. The marketers would simply put them in their shops – people would buy them if they wanted, just like any other product, without any prompting from the shopkeeper.

Thus the marketing system depended on the producer making multiple copies of a video film at his own expense, sticking the photos of the film on the cover and finding a willing marketer ready to accept it on sales-or-return basis. In the beginning, no marketer was willing to either invest in the industry or even purchase the video films directly. They simply stacked them in their shops and gave the producer the sales, after taking their commission. If the video flopped, i.e., with low sales, the producer took the loss. Even if the marketer accepted the tapes, it could take up to six months for the full cost of the video film to be recouped—and even then, in dribs and drabs of at most ₦2,000 at a go. This tied up the producer who had to wait until he collected all the money, or at least substantive enough to start a new production. If a newer, more popular video film came along, the unsold tapes of his film were returned to him.

The tape was often distinguished by a set picture pasted on the cover casing. In this uncertain way, the marketing of the Hausa video film industry started—with no actual marketing—especially advertising, promotion, reviewing, product endorsement—or effective distribution network. It was up to the producers to take copies of the tapes to various marketers in large northern cities of Kaduna, Sokoto, Jos, Zaria, Bauchi, Maiduguri and Gombe. The sheer finance needed for this logistics was simply too much for the early producers and therefore not feasible. It was in fact for this reason that the early-era Hausa video films were produced by associations—Jan Zaki, Jigon Hausa, Tumbin Giwa, etc., who used the umbrella of their organisations to produce and distribute their video films. The producers therefore settled with a simple advertisement on the radio informing listeners where to get a certain release. The marketers, of course, were not interesting in any advertising for any video film—as doing that may draw attention to their illegal pirating activities.

However, when Tumbin Giwa released Gimbiya Fatima in 1992 it became a wake-up call to the viewers and the marketers. This video film opened viewers to the genre, and after a slow take-off period, the Hausa video film had arrived.

Gimbiya Fatima, a period romantic drama in a traditional Hausa Muslim palace, caught the viewers’ imagination and proved so successful that the producers introduced a new innovation in Hausa video filmmaking—making Parts 2 and 3. It was the first Hausa video film to benefit from a continuing story.

New innovations in marketing a Hausa film started in 1995 when Bala Anas Babinlata released Tsuntsu Mai Wayo and instead of a usual set picture of a scene from the video on the cover of the cassette, it had as near a professional quality printed cover as possible at the time. It was the first Hausa video film with a slipcase – or “jacket”, as it was referred locally. This ensured that his video films would be more easily distinguishable. He still had to find his own blank tapes and duplicate the original master and distribute it to the dealers. As usual, the marketers closed ranks and refused to reveal their sources of blank tapes. Ironically, the source was hiding in plain sight – for it was the Indian store along Bello Road called Smarts.

A few months later, Khalid Musa changed all this with the release of Munkar when under Jigon Hausa Drama Club he came up with the idea of giving a master copy of the video film to a marketer, and then selling the number of “jackets” the marketer needed initially at ₦30 per jacket. This meant the marketer would take the responsibility of mass copying of the tapes, slotting them into the jackets and stocking them. The marketer would sell the tape for ₦180—but only the initial ₦30 cost per jacket went to the producer. The marketer’s share was higher because it was his responsibility to purchase blank tapes (at ₦120 per tape) and pay for the duplication. The same sales-or-return policy, however was retained.

By the time Gidan Dabino released In Da So Da Ƙauna to the marketers 1996, they had started showing slight interest in the marketing of the Hausa video films. This was more so because the video film was based on a best-selling novel of the same name and had caught the imagination of Hausa school girls across northern Nigeria and was massively popular – even in the age of the absence of social media. A way still needed to be worked out on mass production of the tapes—which the producers could not afford to do. Gidan Dabino came up with another formula—selling the “copyright” (locally interpreted as the right to duplicate) of the video film for either a year for ₦2,000 or “for life” for ₦5,000. This, however, was specific to a particular marketer.

Thus, as many as five different marketers could all come and lease—for that was actually what it entailed—the copy of the same video film, duplicate it themselves and distribute it as they saw fit. The creative copyright of the video film, however, remained that of Gidan Dabino. This system was not adopted by other producers and the original formula suggested by Jigon Hausa seemed acceptable to the marketers. In fact, it was consolidated when Badaƙala was released in 1997 and the producer sold the jacket to the marketers as per Jigon Hausa formula. Only Ibrahimawa Studios in 2000 with Akasi followed the example of Tsuntsu Mai Wayo of releasing a ready-made video film to the marketers, instead of the master tape. But by then the marketers had cottoned-on the act—the future of Hausa video film marketing lay in the sale of jackets to the marketers. The filmmakers were now firmly in their grip.

The early (1990 to 1995) Hausa video films had a distinct characteristic: they were written mainly by novelists and/produced by structured drama groups and clubs. They were thus artistic in the sense that they were genuine attempts at interpreting the society using a new media technology which was just getting available to young urban Hausa.

For instance, Turmin Danya was a period drama that studied the intrigues of a Hausa traditional ruler’s palace. Munkar was written by a novelist (Bala Anas Babinlata) and a screenplay writer (Khalid Musa), who approached the screenplay with professionalism associated with Babinlata’s widely successful books. It was also a product of a drama group, thus having to undergo through various committees of Jigon Hausa Drama Group before the script was approved for screening. Finally, it had a strong social message—trying to stamp out prostitution among young Hausa girls. In Da So Da Ƙauna, by another successful writer, Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino, explored the essential tension between tradition and choice in marriage by tracing the roots of forced marriage phenomena in one family. Ki Yarda Da Ni was a study of kishiya—co-wife—micro-culture in Hausa marriages. It was adapted from a book by a bestselling author, Bilkisu Ahmed Funtuwa. It thus became the first novel by a Hausa female author to be adapted for video film. It also inspired adaptation of a similar novel that explored the same theme, Kara Da Kiyashi, by Zuwaira Isa, and signaled the entrance of women into Hausa video film phenomena.

Subsequent producers, however, were not novelists, but experienced stage and drama artistes who maintained the tradition of producing their video dramas on tapes and marketing them to an audience that was beginning to become aware of the new popular culture. Within a relatively short period of time, particularly from 1995 to 1999, more producers emerged.

The initial route into the industry was for a newbie producer to give a “contract” to an established producer to make a film for him—or quite often, her—and become involved in every aspect of production. Once the newbie producer had learnt the ropes, he also became a producer, and often a director; not so much for budgetary control of the production, but also to be part of the industry.

Furthermore, in the early stages those individuals who had the capital to form some sort of production companies became easily the market leaders. However, the search for fame and contracts as producers led to the breaking up of these production companies and the Hausa video film industry became an all-comers affair. For instance, in about 1995 Alhaji Musa Na-Saleh, an audio cassette recordist (recording traditional Hausa musicians such as Sani Sabulu, Ali Makaho, Garba Supa) came across Hamdala Drama Group in Wudil during their stage performance.

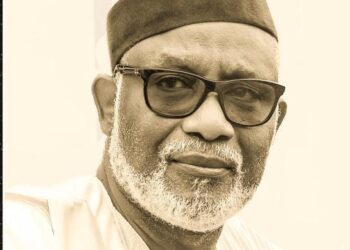

The group featured a comedian, Rabilu Musa Ɗanlasan (1979-2014) with the stage name of Ibro. In a genre-defining business deal, Musa Na-Saleh paid for the production of a comedy by the group featuring Ibro in his first film, Kowa Ya Ɗebo Da Zafi, and established history in Hausa popular culture in two respects. First, it was the first commercial Hausa video film by a marketer and pointed the path to the future of the industry, at least to the end of the decade. Second, it established the Camama genre of Hausa films – cheap, cheerful, realistic extended comedy skits that, quite surprisingly, were true reflections of Hausa social cultures. Indeed, remove the exaggerated body languages of Camama genre actors, focus on the straight storyline dramas and you would have classic Hausa dramas of the 1970s so beloved of older generations of Hausa TV show viewers. It was the least controversial category of Hausa cinema.

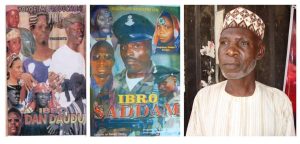

Ibro Ɗan Daudu was a hilarious take on the Hausa transvestite community (‘yan daudu) and chronicled the unlikely union of a “normal” boy to the daughter of a leader of a community of closely-knit “transvestites”. It provided an illuminative insight into how a sub-culture functions and mirrors the reaction of the larger society to the sub-culture. My review of the film became a central feature in Rudolf Pell Gaudio’s classic study of ‘yan daudu in Hausa societies, Allah Made Us: Sexual Outlaws in an Islamic African City (John Wiley, 2009).

Ibro Usama and Ibro Saddam showed how Hausa video film producers interpreted international events. To date they lead as the first Hausa video films to focus on global politics. Even though they were cast as comedies, they were accurate hilarious takes on both American President, George Bush, Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, and the Afghan war in 2002 following the September 11, 2001 attacks on US.

The success of the camama genre of Hausa cinema served as a wake-up call to the marketers. They suddenly realised that serious money could be made out of this new industry, and they decided to move in with their financial organisational power. A last-ditch attempt, however, was made by the industry stalwarts to prevent that from happening through the establishment of film trade associations.