The next Hausa video film—to Badaƙala—to join the rank of catalytic forces to the artistic defining characteristics of Hausa cinema was Daskin Da Riɗi in 1997. It was the first video film to translate a Hausa folktale directly into a film, complete with the traditional songs overlaid with the ever present synthesized keyboard sounds. It also featured singing and dancing between the hero and heroine, but more of a typical disco dancing, rather than an elaborate choreography characteristic of later Hausa video films with direct Bollywood cinema influences.

Daskin Da Riɗi, ironically reflected a sharp change in focus on the part of the production studio, Sarauniya Films. The studio had started with videos aimed at capturing the young market, and mimicking American films such as Home Alone and Problem Child with Hausa equivalents (though not necessarily direct rip-offs) in Tantiri and Gagare and a horror film, Aljana Sumbuƙa. Realizing that the Hausa video film industry was shifting towards incorporating singing and dancing routines, Sarauniya Films decided to follow a different track—by focusing on Hausa folktales, and embellishing their storylines with traditionally-oriented choreography. Daskin Da Riɗi was the first of such efforts, followed by the video that set the road-map for the production studio, Sangaya, which came to be one of the seven biggest selling Hausa video films ever.

The increasing use of “modern” electronic instrument in composing the soundtracks to the video films, especially from 1995 planted seeds of Hindi film music cross-over in the minds of the producers. The Yamaha synthesizer and its multi-instrument sound samples provided an excellent opportunity to re-create Hindi music format, without necessarily ripping-off any specific Hindi film playback music. The Hausa video film Sangaya led the way, produced by Sarauniya Films who wanted to consolidate the massive success of an earlier hit, Daskin Da Riɗi. The specific instrument that brought about this revolution was Yamaha PSR-730 keyboard.

With a vast expanded range of Country, Jazz, Dance, Latin, Rock, Soul and Waltz, the PSR-730 opened up the doors to revolutionizing Hausa “film” music. The first playback song to benefit from its superior range of sound samples was Sangaya from a video of the same title released in late 1999. The song was written by Misbahu M. Ahmad in September 1999 and in October of the same year, it was performed and recorded at Iyan-Tama Multimedia Studios by Alee Baba Yakasai, the keyboardist who replaced the late Nasir Gwale at Iyan-Tama.

Alee Baba, employed by Hamisu Lamiɗo Iyan-Tama as a resident session musician at Iyan-Tama Multimedia, was given total creative freedom – and he used it effectively when composing the Sangaya soundtracks. He had intuitive ear for music, having generated interest in music production from the constant following of Ƙoroso dance ensemble of the Kano State History and Culture Bureau. However, his first mentors on the keyboard were Bala Anas Babinlata – a multi-talented writer, filmmaker and graphic artist – and Mukhtar Kwanzuma, another brilliant keyboardist. Using the Yamaha’s vast repertoire of recorded sound samples, and his interest in Ƙoroso drumming, Alee Baba came up with a masterpiece of modern Hausa Afropop genre in Sangaya. He, unwittingly perhaps, gave rise to “post-modern” Hausa music. By 2024, almost every musical composition in northern Nigeria was based on the synthesizer sound – from advertising jingles, to wedding, political and religious songs. The character of ‘Hausa music’ – that can be attributed to Hausa traditional creativity – has disappeared. Hausa music is now produced by synthesizers and online tutorials, with no character or soul.

Sangaya the soundtrack was released on tape, before the film was shot—similar to the strategy adopted in releasing Badaƙala. It turned out to be a successful marketing move because before the film was even released, the tape of the songs alone, especially Sangaya title track, became a massive hit. I distinctly remember hearing it endlessly looped by a taxi driver who was driving us from Kano to Abuja. He played the tape the ENTIRE journey!!! In fact, that was what made be curious about it, leading to this segment of my fieldwork.

Sangaya contained a traditional storyline with a catchy playback music combining the Yamaha keyboard sound samples over layered with the sampled sounds of traditional Hausa sarewa (flute) and bandiri (tambourine), young and not-so-young popular artistes and a well-rehearsed separate male and female choreographic units. In their desire to replicate Hindi films as closely as possible in the Hausa ripped-off versions, Hausa video producers had to rely on the synthesizer to enable them to create the complex polyphony of sounds generated by the superior musical instruments of Hindi film music. The Sangaya soundtrack would have been impossible with traditional Hausa acoustic instruments that are not accustomed to be being played together in a chamber or symphony music ensemble. I did create Hausa ‘chamber’ music with duman girke, flute, kalangu and kukuma during the Connecting Futures projects with the British Council in Kano, but it did not work out too well. I still have the recordings and might release them one day!

The cinematic motifs of fantasy, desire and passion, were fully exploited in Sangaya. The video film, like almost all other Hausa video films was a love story. However, its multi-instrument approach in its soundtrack borrows heavily from Hindi playback music. It tells the story of a prince who falls in love with his maid and plans to marry her. The other maids in the palace, out of jealously and spite, put a jinx on her which made her go away from the palace as dove (“kurciya”, the name of the spell, which is also dove in Hausa).

The by now increasingly obligatory song and dance routine of the leading playback song, “Sangaya”, made the video film a massive hit (and years after its release, still popular, a feat among Hausa video films whose appeal last till the next release which could be just days apart). Although Hausa video film producers are extremely reluctant to reveal their sales figures, the producer of Sangaya estimated that Sangaya sold at least 60,000 units. This made it the most long-term commercially successful Hausa video film up to that time (mid 2000).

The synthesizer business in Kano therefore blossomed. Iyan-Tama Multimedia studios purchased a higher Yamaha PSR 740 in 2001. By then other music studios had been established in Kano. These included Muazzat, Sulpher Studios, and in Jos, Lenscope Media. Sulpher Studios, in addition to Yamaha PSR-2100, also use Cakewalk Pro music software. Between them, and pioneered by Iyan-Tama Multimedia, these studios effectively created Hausa Afropop genre of contemporary music in a traditional society. This, in turn, totally eclipsed and smothered traditional Hausa music genre which is based on acoustic, natural, instruments such as kalangu, sarewa, gurmi, garaya, duman girke, kukuma, and others.

The availability of these modern studios opened up a whole new range of services for individuals interested in music—not just video film producers. Thus, Islamiyya school pupils, who had hitherto remained vocal groups and often drawing on Hindi film song meters to sing the songs in the praises of the Prophet Muhammad, joined in the act, and started using the Yamaha sound for their recordings, which were sold in the markets.

In a fascinating cross fertilization of influences, the Islamiyya school ensembles stopped using meters from Hindi film songs and started using the meters of Hausa video film soundtracks. Thus soundtracks from popular Hausa films such as Sangaya, Wasila, Nagari, Khusufi, were all adapted by Islamiyya pupils, often with Arabic lyrics. Although this process of modernization of the Hausa video film song sequence is extremely successful because the video film producers make more from films with song and dances than without, there are often dissenting voices about the intrusion of the new media technology into the film process, with the objections being against the killing-off of Hausa traditional griot music genre.

By 2004 the strongest selling point for a new release of Hausa video film was hinged on a trailer that captures the most erotic song and dance scenes, not the strength of the storyline (which remains the same love triangle in various formations). Examples of video films that caused such furor with their erotically provocative trailers included Biki Buduri, Farin Wata, Lancika, Baƙar Ashana and Hamdan. Consequently, a Hausa video film without song and dance routines—and the more erotically provocative, the better—is considered a commercial suicide (e.g., Hafizu Bello’s Ruhi), or artistic bravado undertaken by few bohemian filmmakers (e.g. Bala Anas Babalinta’s Tsuntsu Mai Wayo, Sunusi Shehu Burhan’s Dace Da Masoyi) or those with enough capital (e.g. Iyan-Tama Studios with Ƙin Gaskiya) to experiment and not bother too much with excessive profit. Indeed, the most commercially successful Hausa video films (e.g., Sangaya, Taskar Rayuwa, Salsala, Wasila, Kansakali, Ibro Awilo, Mujadala), succeeded precisely because of their song and dance routines, rather than the strength of their storylines or their messages.

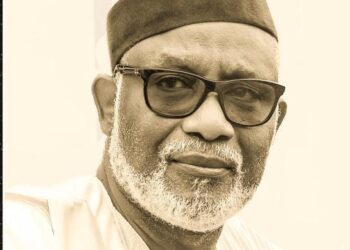

* Abdalla Uba Adamu is a double-Professor (of Science Education, and Media Studies) at Bayero University, Kano. He is a former Vice-Chancellor of the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN)