For the last few weeks, I have been chronicling the story of Hausa Cinema in its first decade from 1990 to 2000. I am putting the entire series together as a single file and will share it at the next posting.

As I indicated in earlier posts, this is part of a book I have written in 2005 and is now revised for publication in 2025. I am sharing the first chapter to shake the tree and see what falls out after 20 years from the first writing. So far, not much (just a single disagreement over vanity). I will explain further in my next post, which will detail my field strategies.

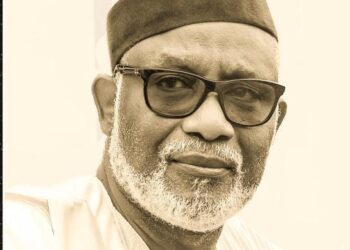

I named THIS posting ‘coda’, which is “a concluding segment of a piece of music, a dance, or a statement.” It is the last I will post on Kannywood, now or in the future. It differs from the others in two aspects. First, it was about Hamisu Lamido Iyan-Tama. He was not part of the ‘founding’ fathers of Kannywood – coming along almost six years after the industry had started. He was riled and reviled for this.

Second, his non-participation in the early stages of Kannywood, indeed, his non-participation in the Hausa media industry in the first place, gave him a massive advantage over those ‘sons of the Kannywood soil’. He was independent, and therefore free to do whatever he wanted. In this process, he gathered a group of creative individuals and from 1996 to 2004, they produced the most innovative and original films in Hausa cinema history. This earned his company more awards and international recognition than any Studio in Hausa cinema history. Any reference to ‘real Hausa films’ is almost always to the products of Iyan-Tama Multimedia era Hausa film production.

*

A quiet sunny day in Sabon Gari market Kano in 1993. Ɗan Azimi Baba, who was a novelist, producer and filmmaker, was in the market visiting a friend. As they were talking, a gentleman passed by and hailed them, since he knew Ɗan Azimi ’s friend. After he had gone, Ɗan Azimi became curious about the gentleman and asked his friend who he was. He was told his name and indeed, he even had a stall in the market – a boutique. He was an international business man, selling high quality imported clothing and textile from the Middle and Far East. Ɗan Azimi was stuck by the man’s personality and charisma. As a film producer and member of the Raina Kama Writers Association, he immediately saw the man as a movie star. He asked to be taken to the man’s shop where, after introducing himself, he told him he wanted him to feature in a film he was producing. The man was amenable, but on one condition – the proposal has to have the blessings of his mother.

So off they went to the mother where the man introduced Ɗan Azimi and explained the latter’s proposal. He stated that he will accept only if she approved and blessed the move. She instantly agreed, blessed him. There and then, a star was born. He was Hamisu Lamiɗo Iyan-Tama.

Without any doubt Hamisu Lamiɗo Iyan-Tama remained the most charismatic, innovative and elegant film star in the Kannywood universe. Understandably, as a human being, he was imperfect in some respects – for instance, his domineering attitude and what people see as self-centeredness, often led to disagreements with associates. He was, however, focused in terms of filmmaking. He had no prior background in drama club membership or literary experience . All he had were his towering and imposing looks, powerful personality, and wealth, and willingness to use his wealth and chart new directions in Hausa filmmaking. His non-membership of earlier Kannywood ecosystem gave him a massive advantage to be creative and chart an independent original trajectory for his films. He was taunted for it, and this made him to eventually join Jigon Hausa as his own initiation rite.

Ɗan Azimi was already a member of the Raina Kama Writers Association who branched out into filmmaking. His encounter with Hamisu enabled him to produce Bakandamiyar Rikicin Duniya with Hamisu as the lead. It was hugely successful and established Hamisu as a film star. After the wrap-up, Ɗan Azimi brought in two other associates, Bashir Mudi Yakasai and Nasiru ‘ɗan aljan’ Gwale and the eventual establishment of Iyan-Tama Multimedia Studios company.

Hamisu subsequently invited others to join him and they collectively formed a loose Bohemian – “a socially unconventional person, especially one who is involved in the arts”, in case you want to know – cluster of innovators, intellectual rebels and charted the direction of what Hausa cinema should be. This is a filmmaking that reflects the cultural ecology of Hausa societies – and I would believe, even equated to West African greats such as those made by Ousmane Sembène (Senegal), Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (Chad), Souleymane Cissé (Senegal) and Idrissa Ouédraogo (Burkina Faso). Pure African filmmaking. No Indian rip-off or appropriation. No baseless singing and dancing. Filmmaking so authentic it is custodial to the culture of the people being depicted. Hamisu’s expressive power as an actor was brought to forth in Ƙilu Ta Ja Bau, his most famous role that brought him out as an actor. Badaƙala was produced under his company, but it was essentially not his story.

At an event in the Public Affairs section of the US Embassy in those mid-1990s, my opinion was sought about the best filmmakers in kano. I unhesitatingly pointed to Iyan-Tama and his Bohemians. The term itself – unusual in Nigerian literature – caught the attention of the officials. This was to later form the basis of partnership between Hamisu and the US Embassy.

Those who formed Hamisu’s Bohemians included Bashir Mudi Yakasai, Sunusi Shehu, Ahmad Salihu Alkanawy, Bala Anas Babinlata, Ɗan Azimi Baba, Khalid Musa, Nasir Gwangwazo, Tijjani Ibraheem and Alkhamees D. Bature. Most were hugely successful creative fiction writers who migrated into the visual medium. They formed a loose coalition of scriptwriters, directors or producers from 1995 to 2004. Their Bohemian cluster produced experimental films without regard to commercial viability.

Iyan-Tama Studio’s storylines focused mainly on the domestic ecology of Muslim household and struck a chord in many families. They also introduced the innovation of premiering their films to select Ulama (Islamic clerics) to ensure conformity with Islamic principles before releasing the film to the market. Their premier reviewers included the late Sheikh Jafar and the late Yahaya Faruk Cheɗi.

Under the platform of Iyan-Tama Multimedia, these unsung Hausa public intellectuals gave the studio its distinct focus and sermonizing direction in films. Between them and in the years they were active, they had produced 24 films. These included Gashin Ƙuma, Fallasa, Buri, Halak, Alƙawari, and Aisha. Some of the films were premiered at international film festivals, as a show of what the best of Hausa cinema can be.

Tsintsiya, for instance, fully sponsored by the US Embassy in Nigeria, was screened at the Nigerian Universities Commission (NUC) Auditorium in collaboration with US Diplomatic Mission under Robin Renee, the then US Ambassador to Nigeria. It was also premiered at the Nollywood North American Film Festival, Toronto Canada, as well as Canadian Film Centre, and Subversive Film Festival, Croatia and Queen’s College, Goa, India. It was the first Hausa cinema film to attain these honors. Another film, Haƙƙi, was premiered in Kano on May Day 2018 due to its focus on labor relationships as it was in partnership with the Nigerian Labour Congress, Kano.

The studio also broke new ground with the first legal thriller in Kannywood, Ƙin Gaskiya and Maras Gaskiya, featuring a stand-out performance by Farida Jalal. The film (basically one film, but split into two court cases) was the first in which the actual Supreme Court premises in Abuja were used by any filmmaker in Nigeria.

This eventually led to Iyan-Tama being engaged by the US Embassy to shoot an advocacy film, “Rashin Sani”, on HIV awareness in 2005. The success of the film led to a larger engagement in shooting “Tsintsiya”, an adaptation of West Side Story (dir. Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise, 1961). The film won the 2008 Zuma Award for best film on social issues. It was at a meeting between myself, Hamisu and State Department officers about the future directions of Hausa video films, that I brought up the idea of ‘return back to basic’ Hausa filmmaking that focuses on social issues, instead of the endless and fruitless romantic stories characteristic of KanHowev.

However, like in any group of highly creative people, eventually tensions and disagreements among Iyantama’s Bohemians started to manifest themselves. But while they were still together, they were joined by Hamisu’s elder brother, Ahmad Sarari, who also has keen interest in filmmaking and was willing to go beyond any boundary of creativity. When it was clear that the group could no longer sustain itself, it imploded. Hamisu closed the group in 2004 and eventually redistributed the equipment into various locations in Kano.

Dr. Ahmad Sarari, as he was known eventually, took over the Bohemians when Hamisu virtually disbanded the group. Ahmad, with immense focus on excellence in medical matters, started producing films with critical focus on social responsibilities in health, one of them being Waraka which explores other ways of contracting HIV beside sexual intercourse.

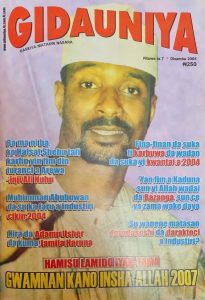

Subsequently, Hamisu migrated to politics with intention of contesting the 2007 Gubernatorial Elections under the platform of New Democratic Party. That put him in direct collision with the mainstream political parties in Kano. Mysteriously, copies of Tsintsiya found their way into a video store in Kano, and Hamisu was arrested by the Kano State Censorship Board on the charges of releasing an uncensored film, and alleged failure to register his production company with the Kano State Censorship Board. This, despite the fact that Tsintsiya was released in Kaduna, and had ‘not for sale in Kano’ boldly written on it. Further, Iyan-Tama Multimedia had been in existence with Corporate Affairs since 1997.

He was arrested on May 10, 2008 and charged to a special mobile court created to try cases relating to the Hausa film industry. The judge refused to grant bail and ordered the remand of the accused person in police custody until Monday, May 12, 2008. Subsequently, he was imprisoned for three months by the Kano State Government on earlier charges and ordered to pay ₦300,000. After a long drawn-out legal battle that was beginning to attract unwarranted attention to the Kano State Government (including a Free Iyan-Tama Campaign by the US Embassy), he was cleared.

He almost immediately produced and released a film, Kurkuku [Prison] which presented his side of the saga of his arrest and subsequent court cases. He did that to expose the injustice filmmakers suffered under the then Kano State Censorship Board.

Hamisu Lamiɗo Iyan-Tama has put his mark on the Hausa cinema by being creative, innovative and experimental. His films and approach to filmmaking would have proven the signposts to the greater heights Hausa cinema can go, nationally and internationally as representative of the cultural ecology of Hausa people. Regretfully, his Bohemian approach was swept away by the tides of transglobal appropriation based on Hindi film cinema copying and masquerading as “New Kannywood” in contrast to his Bohemian “Classic Kanywood”. And the difference in the spelling is deliberate – the Bohemians always refer to the Hausa film industry as Kanywood, not Kannywood.

A documentary film on The Iyan-Tama I Bohemians of Hausa Cinema would encapsulate all that is classic Hausa cinema in its first decade. I believe Iyan-Tama owes Media Studies communities in making this documentary himself.

* Abdalla Uba Adamu is a double-Professor of Science Education and Media Studies at the Bayero University, Kano