Say what you can, but Kano has always been innovative. I am currently revising a book on the history of Hausa cinema for a publisher in the United States, so I want to share a few morsels of information that might be interest, and also give depth to the history of Hausa cinema in the light of the current (November 2023) real-life drama that is playing out in the industry.

What is known as Kannywood has an original name “Finafinan Hausa”. It professionally started in 1990, but amateurishly in 1980 when it was kick-started by Sani Lamma and Hamisu Gurgu of Kano (more of them in subsequent postings). In 1990 it was the brain child of late Aminu Hassan Yakasai, supported by Aminu Hassan Yakasai, Ali “Kallamu” Muhammad Yakasai, Bashir Mudi Yakasai, and Tijjani Ibraheem. Their first film, , released in March 1990, was directed by Salisu Galadanci. This was the beginning of what is now known as Kannywood.

The halcyon Hausa cinema days were days of joy, fame and stardom. Two storylines dominated the films. The first focused on domestic ecology of Hausa marriages. This was led by Hamisu Iyan-Tama group of Bohemian writers, including Ahmad Salihu Alkanawy, Khalid Musa, Bala Anas Babinlata, ruled the roost. Iyan-Tama led the group – an easy thing for him to do since he remains the most innovative, experimental and charismatic filmmaker in the history of Kannywood. The first filmmaker to shoot inside the Supreme Court. A second layer of storylines was led by Ɗan’azimi Baba Ceɗiyar ‘Yangurasa, dealing with urban sociology. No singing. No dancing. Just solid storyline that talks to you and your environment.

Media coverage of the new entertainment was covered by basically fanzines, that later became magazines, giving tidbits of the film industry. No one was making much money, but what they lack in money, they made up in instant recognition wherever they go. They were feted and sought as simple socialites. No airs and graces.

The transformation came in 1999. First, a magazine, Tauraruwa, founded by Sanusi Shehu Daneji, a writer, started a column he called ‘ – making him the first person to create the term. This was a revolutionary moment in African media history. It was the first time an film industry was collectively named. Kannywood was not meant to imitate Hollywood in film ethics. Indeed, it was more like Bollywood, because the magazine, Tauraruwa, cloned an Indian film magazine called Stardust.

The name was almost talismanic – it was certainly an auspicious beginning of the film industry. Unfortunately, it also paved the way to its future. In October 1999, Sarauniya films released Sangaya. It was undoubtedly the most iconic film of its period, and for the fourteen years, it opened the floodgates of Indian cloning of choreographed singing and dancing. This was radical departure from the more sober films of the 1990s. Arewa 24, a satellite TV with heavy dosage of TV shows delivered in series changed the landscape of Hausa cinema when it debuted in 2014. While the series had a suspiciously Zee World veneer, the storylines harked back at the pre-Sangaya narrative – thus making them less objectionable.

So, in 1990 Tumbin Giwa Drama Group in Kano released Turmin Danya. There was no video film industry as we know it then. Ola Balogun, Jab Adu, Moses Olayia, Eddie Ugboma and Hubert Ogunde were pioneering celluloid filmmakers. The southern Nigerian video film industry was born in 1992 with Living in Bondage. The term Kannywood was coined in 1999. No other film industry in Africa had any name. In 2002 Norimitsu Onishi of The New York Times coined the term ‘Nollywood’ to reflect the southern Nigerian video film industry.

“When a man is tired of living in Kano, he is tired of life”

*

Update: The Politics of Kannywood Naming

I am absolutely blown away by the number of reactions to my short posting on Kannywood naming! Thanks to you all – both who ‘Liked’, those who commented favorably, and those did not. It is very stimulating, since according to my old teacher, Karl Popper, knowledge only grows with criticism. Alhamdu lillah.

I want to use this follow up post to clarify few things that emerged from the debates. Using Victor Turner’s concept of the ‘anthropology of experience’, I embedded myself in the Bohemian community of writers, filmmakers and artists in Kano centred around City Business Centre in the 1990s. This was after declaring ‘career suicide’ and started migrating from Education to Mass Communication in 1996. I was warmly received by the Bohemians so they had stories to tell, and they want to tell their own stories.

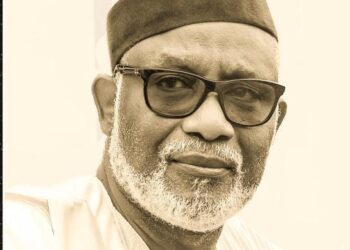

As noted, Sanusi Shehu Daneji came up with the name ‘Kanywood’ in a Tauraruwa magazine column in August 1999. In its December issue of Fim magazine (established by Ibrahim Sheme and his friends), Bashir Mudi Yakasai, a foundation member of the Hausa film industry, created a column he titled (photo attached). Published in Kaduna, Fim remained the single most consistent objective source of information about the industry since its first issue in March 1999. Professionally produced, with an almost academic flair for balance and less sensationalism, it rapidly became the leading and authoritative Hausa video film magazine in Nigeria and beyond, complete with an independent web site.

Soon, we had two ‘woods’ in 1999 – Kanywood and Kaliwud. Now, things then started getting fuzzy in the competitive desire for readership and hegemony. Fim magazine quickly dropped “Kaliwud” – they have never accepted “Kanywood” and refused to use the term before coming up with “Kaliwud” – and introduced Kannywood – with TWO ns! It was not clear precisely when this was done, but it was certainly after December 1999 since that was the debut of “Kaliwud” (the next edition of Fim after this issue was March 2000).

Further, instead of “Kanywood”, Fim started using ‘industiri’ as a label for the industry. It was much later – and I still can’t locate the first usage, that Fim started using “Kannywood”.

Due to the persistence of Fim magazine – it has wider distribution network throughout the country and Niger Republic and its utter professionalism – the term “Kannywood” gradually became dominant. With the collapse of Tauraruwa magazine, the term Kanywood died.

Academically, we continued using Sanusi’s “Kanywood”, in recognition of its being a pioneer tag. However, almost everyone uses “Kannywood” – indeed, many people did not even know of the original term, as it was lost in the virus that afflicted dozens of Hausa film magazines that sprouted up in the period. Only Fim magazine survived up to this day.

Without muddying things up, I started advocating for, rather than clonish Kannywood as a label to designate films made by the Hausa wherever they are. We had a very lively WhatsApp debate with Ibrahim Sheme on this issue, each of us with differing reason. While the woods – Hollywood, Bollywood, Nollywood and Kannywood – represent locational activity, Hausa films go beyond location now. My reason was simple – Hausa film is no longer tied to Kano. Filmmakers in Kaduna have already rebelled by creating, I think, Kadawood, or something along those lines. So, what next? Zamwood, Katwood, Zarwood? It’d be getting ridiculous.

My logic is that we are dealing with cultural representation through the film medium – and Hausa are all over the place, far more than any ethnic group. Some have never been to Kano. For instance, there is a vibrant Hausa community in Hamburg, Germany; even the Friday Sermon was in Hausa/German. Yet none of those I met during my visit has ever been to Kano, nor were they Nigerians. If they make a film, and it will be in Hausa, will it still be labeled Kannywood?

Language, therefore, became the criterion – same as French Cinema, Russian Cinema, etc. Some producers have tried English films by Hausa actors. The earliest was by Adamu Muhammad Kwabon Masoyi with the Houseboy. Then Wasila in English. Later Jammaje got into the act with This is the Way. None of them was sustainable because somehow Hausa audiences believe a Hausa film is in Hausa language – thus showing the persistence of the language.