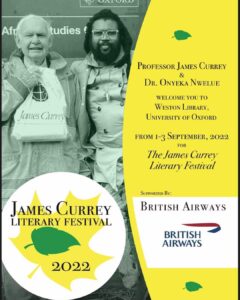

Breakfast at the Hall of Wadham College, Oxford University, UK, was a routine meeting place for many of the delegates to the maiden edition of the James Currey Literary Festival. Organised by the young and energetic Nigerian writer and academic, Onyeka Nwelue, the festival was to honour the contributions of Professor James Currey, co-founder of the famous African Writers Series (AWS).

Tucked away in a corner of the claustrophobic bowel of the college, which was established in 1610, the hall was busy that early morning as writers from all corners of the world tucked into the typical English breakfast of eggs, bacon, sausage, toast and tea.

As we ate and chattered in a warm camaraderie that is typical of writers’ events, some of the famous alumni of the University College stared down at us from the paintings hung on the walls of the cavernous ancient hall. Amongst Wadham’s most famous alumni are Sir Christopher Wren, one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history who was also an anatomist, astronomer, geometer and mathematician, as well as the broadcaster, novelist and actress, Rosamund Pike.

Established in 1096, Oxford University is the oldest university in the English-speaking world and second oldest in the world after the University of Bologna, Italy, which was established in 1088 and reputed to be the oldest university in continuous operation in the world. Oxford is also said to run the world’s largest university press, the largest academic library system in the country, as well as the oldest university museum.

To reach the university, which is located in Oxford city, 90 km northwest of London, which was my working base on the trip, I had to take the train from Paddington Train Station. As I heaved my luggage, which consisted mainly of books, into the crowded train at Dagenham East station for the one-hour trip to Paddington, I was both alarmed and at the same time excited at what I saw.

After a two-year hiatus brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was a delight to resume my international traveling routine. As a regular visitor to London, I used to be impressed with the sight of train commuters keeping themselves busy reading newspapers, magazines and novels.

However, rather than bury their heads in printable material, most of the commuters on the train to Paddington that early September morning were glued to their phones, I-pads, tablets and apps of different brands and colours.

And, as they twitted, flipped switches and browsed away, the expressions on their busy faces ranged from anger, laughter to deep concentration. Judging from the fact that commuters of all ages were involved in the electronic exercise, it was obvious that the digital age has finally caught up with the young and the old.

As I surveyed the breadth and length of the train with its ‘digital readers’, my book-laden luggage briefly felt out of place. It did not matter that I was going for a book festival where I would meet some famous members of the book industry ranging from writers, publishers, printers and booksellers. It did not also matter that I was going to Oxford to witness the release of the UK edition of my new book with the endless possibilities of exposure to the international literary market, literary prizes and other ancillaries for my literary career.

All that mattered to me at that time was the fear of a gradual demise of the book, no thanks to technology.

Another interesting observation on the train was the enormity of London’s mixed racial population. Although, historically, London has always been composed of a mish-mash of races drawn from every corner of the globe, according to recent statistics, the city has now become one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world. Over 300 languages are now spoken in Greater London.

At the 2011 census, Greater London had a population of 8,173,941. Of this number 44.9% were white British. 37% of the population were born outside the UK, including 24.5% born outside of Europe.

Apart from the well- known teeming population of Asians, Africans, Caribbean and other white immigrants, intermarriages among these races have gone on to produce a new generation of British citizens with ‘colours of the rainbow’.

Even though the fast evolving new metropolis had been predicted many years ago by demographers, The Sunday Times 2018 report that “Britain has the highest rate of interracial relationships in the world” took many sociologists by surprise.

It was therefore not surprising that above the clattering and screeching and rumbling of the Paddington-bound train, a medley of different languages, ranging from English, Indian, Spanish, German to some African languages such as Yoruba, Hausa, Twi, Igbo, among others, floated in the rarefied interior of the carriages as commuters spoke into the ubiquitous cellular phones.

About two hours later on arrival at the Oxford University venue of the book festival, it was obvious that my observation on the train that early morning about the new reading inclination of many people was very well known to the literati that attended the literary event. As the lively programme progressed, writer after writer harped very strongly on the need to embrace digital publishing in order to keep up with the new literary order.

It was the US-based Nigerian literary activist and book critic, Ikhide Roland Ikheola, who put it very succinctly. While delivering the James Currey Lecture on the second day of the three-day event, Ikheola called on African writers to embrace digital publishing in order to be in tandem with global developments.

As he put it, ‘’On balance, the West has been supportive of African literature, but the Internet and social media house authentic African narrative, unlike the sanitised gruel from many traditional Western publishing houses. We must revive the African narrative organically.”

Later in the evening, I decided to take a walk round the university, which has consistently played a big role in the education of many African scholars, politicians and writers. These include former Ghanaian presidents Edward Akufo-Ado and John Kufour, the former Nigerian soldier and politician, Emeka Ojukwu, and Bram Fisher, the lawyer who defended Nelson Mandela during his political trials, as well as the famous Nigerian writer, Diran Adebayo, among others. It is equally important to note that Lady Kofoworola Ademola from Nigeria was the first black woman to graduate from Oxford.

My sightseeing commenced at Waldahm College where I had stayed with some of the writers in the clean and modest dormitory.

As I admired the ancient buildings around the front quadrangle, including the chapel and the Hall, I was impressed by the medieval and symmetrically built buildings. I later learnt that the buildings, which were built around 1609, are Jacobean in style. They were designed by the famed architects, William Arnold and Sir Christopher Wren.

As I roamed through the cobbled and claustrophobic side streets of the ancient institution, with its array of medieval but well preserved buildings, I reflected on the importance of the preservation of archival material, be they of structural, literary or visual arts background. Since it was impossible for me to visit all the 38 colleges that make up the university, I was contented with the few colleges I could visit.

Away from bustling London, the iconic buildings of Trinity College, Queens College, and Waldheim College among other colleges, stood in majestic grandeur in the September twilight as a fitting testimony to more than 1,000 years of Oxford’s diverse history and heritage.

I returned to London via the same Paddington train station to the blazing headline news of the election of the new British Prime Minister, Elizabeth Truss. Perhaps what attracted more public attention was the fact that the new prime minister had selected a cabinet where for the first time in the country’s history, a white man did not hold any of the country’s four most important ministerial positions.

While Kwasi Kwarteng – whose parents came from Ghana in the 1960s – is Britain’s first Black finance minister, James Cleverly whose mother hails from Sierra Leone but whose father is white, is the first Black foreign minister. Suella Braverman, whose parents came to Britain from Kenya and Mauritius six decades ago, is the second ethnic minority home secretary, while Kemi Badenoch of Nigerian parenthood but married to a white Briton, is the minister of international trade.

Despite the fact that the upper ranks of business, the judiciary, the civil service and army are all still predominately white, this new development elicited different reactions from different quarters.

My British friend, Alistair, who is now a retired CEO of a Nigerian-based multinational organisation, was not happy with the development. Alistair, who had invited me to lunch at the Old Bank of England on Fleet Street one rainy afternoon, was piqued that the four most powerful positions in the cabinet of the new British prime minister had gone to people of colour.

Alistair also complained that many nefarious behaviours, ranging from knife-stabbing incidents to election malpractices, which were hitherto unknown to British culture, have now become commonplace. ‘’I am not a racist,’’ Alistair contended. ‘’However, I believe that the owners of a country should be in control of their country and not foreigners.’’

On the other hand, many members of the Asian and African communities are happy with the rising profile of their kith and kin in the UK. Malik, the elderly Pakistani cab driver who took me out on one occasion when the rain from the unpredictable English weather had prevented me from taking the bus, was ecstatic with joy. Flashing me the photograph of his first son, he said, ‘’He had a first class degree in Economics from the University of Kent and is currently in Oxford University for his masters. Maybe, one day, he may become the British Prime Minister!’’ He chuckled.

Since football is an integral part of English tradition, one sunny day, in lieu of watching a football match, I decided to visit the home of one of my favourite football clubs, Tottenham Hotspurs. The Tottenham Hotspur Stadium is located in the northern suburbs of London. Built in place of its former White Hart Lane Stadium (1899-2017), it has been the home of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club since April, 2019.

As I went round the magnificent edifice, which is said to have cost the whopping sum of 1 billion pounds to build, I was informed that apart from football matches, the facility is also used for concerts, conferences and events.

After several days of eating ‘Oyinbo’ food, I hungered seriously for some African/Nigerian food. I therefore went in search of a Nigerian restaurant. Fortunately, I found one in Barking, East London. I was surprised at the array of Nigerian food on the menu, especially the different types of soups. I was just cleaning up my plate of ‘Amala’ and ‘Ewedu’ laced with an array of assorted beef when the television set tucked into a corner of the restaurant announced the passing away of 96-year-old Queen Elizabeth.

Coming just a few days after the emergence of a new Prime Minister, the death of the Queen and the subsequent crowning of a new King was definitely a momentous time in the history of the UK. Even though she lived to a very old age, the UK and many parts of the Commonwealth went into mourning at the news of her death. While the front page of the London Daily Express read, OUR BELOVED QUEEN IS DEAD, the Daily Mail, in its “historic special edition”, ran a tear-jerking headline: OUR HEARTS ARE BROKEN.

Although a double rainbow was said to have appeared over Buckingham Palace moments after the announcement of the Queen’s demise, I missed what the Daily Mail described as “a glorious splash of colour in the grey afternoon sky” due to my gastronomic assignment in the Nigerian restaurant.

And so it was that I took off to Buckingham Palace the following morning to join other mourners to pay my respect to the late Queen Elizabeth II.

Even though the announcement of the passing of the British great grandmother was less than 24 hours old, I met hundreds of mourners who had defied the heavy early morning rain to pay their respects to the woman who many had described as UK’s “guiding light in the darkest of nights.”

Many brought bouquets, which they laid at the black iron gates of the iconic building where a notice announcing the death of the only monarch most Britons have ever known was attached.

Back to my base later in the day, my daughter asked me to help look after my two grandchildren while she quickly kept an appointment somewhere in town. It’s no secret that grandparents love to dote on their grandchildren, so when presented with my first opportunity to babysit, I was happy to oblige. Little did I know what I was up to. Hardly had their mother left the house than the hitherto quiet and mild looking toddlers took off in different directions in the house.

While the four-year-old boy ran up a double bunk bed from where he wanted to jump in a ’super man’ style, his three-year-old sister ran into another bedroom, brought out the drawers from her mother’s dressing table and scattered all the contents on the floor.

Grandpa was left with running from one room to the other trying to maintain order and safety while the toddlers shrieked about the house with delight. Within minutes, I was exhausted.

As I wearily sat down to catch my breath, my four- year-old grandson came over and gave me a big hug. ‘’I love you, Grandpa. You are my best friend,’’ he said, his young face radiant with a wide smile, as bright as the London afternoon sun that floated through the lacy curtains into the house.

* Dr Okediran is the President of Pan African Writers Association (PAWA)