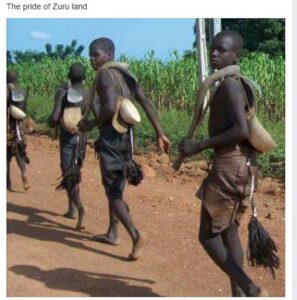

Brain and brawn is what nature and nurture has endowed on the people of Zuru Emirate located in Kebbi State in north-western Nigeria apart from its admixture of religious pluralities involving an estimated 50% Christian, 40% Muslims and 10% traditionalists. It was to knit this diversities that gave birth to Zuru Emirate Development Society (ZEDS). But these people are also enmeshed with the lucre of hard work and venison consumption.

Today, it is difficult to find games in all the plains, sahel grassland and hillocks of the area as they have either retreated or were decimated by the skilled archers.

It is this craving for meat that made their Hausa neighbours to derisively describe them as “komai nama, har da tayar mota” meaning everything is permissible as meat including motor tyre. They were oblivious that animal totem were left untouched.

However, the remarks only represents an ancient inter-tribal banters as the Lelna correspondingly also describe them as Cogno, meaning empty vessel of a shear butter nut devoid of viscosity which depicts them as noisy and empty vessels.

Actually, game hunting like the other marital activities of the people came about as a result of a cultural background that is steep in honour-seeking. For a man to transit to an Okno (ancestor) worthy of veneration, he must have bagged lifetime awards. This involved killing a big game like Buffalo to earn the hunting title of C’tage that goes with Ch’im-chima renowned hunters drum beatings.

Also, in the course of rendering seven years farm service to his potential in-law of his betrothed called Golmo, a suitor is required to produce substantial number of rats and rabbits with which to consume his meals for the period. And in both the D’biti (planting season) and Uhola (harvest season) festivals, there is archery competition in addition to wrestling. Organised hunting (Hiri) and individual hunting (Hobo) are also carried out.

Also not out of place is the contract or mercenary hunting to assist a non-Lelna community being ravished by a feral animals destroying farms and stalking domestic flock and birds. In fact, according to Amos Bawa (2020) in his Zuru culture book, kilishi (skimmed meat) was first prepared by a Zuru hunter named Kalshi based in Gwandu who was an expert in sa’re (meat sun drying. He became popular with the Hausa-Fulani, who handed over their sick cows, goats, ram and sheep to slaughter and prepare Sa’re. In exchange they gave him salt or potash. That was how Kalshi stayed behind in Gwandu and had his sa’re turned to his name due to pronunciation gap.

Meanwhile, his people had migrated to the forest and camped in Boɗinga, Gummi, Aliero and thence to Alela (Zuru territory). Little wonder, all games in Alela had retreated to Lower River Niger trough into the Borgu Game Reserve, Kamuku National Park, Kuyambana Game Reserve, and Kainji Lake National Park. This could have been the result of centuries of freelance human predating and deforestation.

In short, climate change did not start today. Perhaps, this stalking also include those of edible leaves whose tendrils have been harvested for the popular Jab’jabi vegetables soup steeped in over-aromatic C’wande and C’landa daudawa spices.

The parks have been over-stretched with the herculean tasks of containing and warding off poachers. It was this hunting prowess that was recognised by WAFF who had engaged the people during the scramble of colonialism which culminated in the establishment of a military depot in Zuru. For, according to colonial officers, the people were not only brave and loyal, but were splendidly built physically.

To masticate the hardest bone meat, a Zuru man’s teeth is carved to the tilt, for beauty and identity which also assist him in using the sharp edges. This black smitten skill achieved in carving the blade that is used were performed by the Zogne (blacksmith clan) who prepare them from tama (iron ore) found in abundance in parts of Alela. This body scarification also makes the men fearsome wrestlers and archers.

So, the present fashionable body tattoo did not start today. One of the natives, the late Col. Muhammadu Manga, had excelled in this target shooting competition becoming at one time the World Military Archery Champion.

An interesting aspect of a Zuru man’s world view is the penchant for the supernatural either through herbalism or the Abrahamic religions. Thus the resort to ‘medicine’ from herbs, barks, roots and hides and skin started when the Golmo (marital farm brigade) initiates were undergoing the engagement rites. The Gov’din Golmo, Commander of the Golmo academy, instructs them on the use and misuse of herbs to fortify themselves.

And with incessant raids by bandits, slave riders, colonialists and Jihadists, as well as Hiri hunting into thick forest for months on end, they believed there was no need to play God to avoid becoming victim of ‘black spirits’, enemy clans and hunters turn animals and vice versa. It is this belief and practices that made them brave soldiers and dakaru (warriors) from where the insufferable description of Dakarkari was derived to name the ethnic group instead of Lelna.

Also the natives have this traditional code of honour (Har Ya’emte) depicting ‘No Turning Back’ on pacts, as it is regarded as being cast on stone. It is a coded world view of eternal bondage and agreement never to be broken.

A Zuru man is, therefore, not expected to go back on his words based on voluntary pledge. This also explains why the Zuru man can be trusted as loyal and obedient soldier and bodyguard during the Songhai Empire, Kebbi Kingdom, and British WAFF and in the Nigeria Army.

It is also equally on this note that he does not go back home when he leaves to search for the better life outside, as it is still to him ‘forward ever, backward never’. It is based on this behaviour also that their Hausa neighbours again developed the maxim of ‘shiga sojan Badakkare’ to depict non-compromise and refusal to change one’s mind. This insinuates that given the opportunity a Zuru soldier does not favour retirement as he is in love with the physical nature of the work akin to his initial Golmo training.

A people in search of fame from the use of their brain and brawn, the Zuru Emirate has, according to Atom Turba (2021), produced over 60 professors, 100 doctors, 60 generals of equivalent ranks in Army, Air Force, Navy, Police, Customs & Excise, Immigration, Prison, NCDC, FRSC, etc.

To mention a few of these Zuru VIPs, we will include Professor Ishaya Tanko, Vice-Chancellor, University of Jos; Professor Abdullahi A. Zuru, former Vice-Chancellor, Usmanu Danfodiyo University (UDUS), Sokoto, and INEC Commissioner; Professor Abubakar A. Zuru, Chairman, Unipetrol, Warri; Major-General (Dr) HRH Sani Sami, a former Governor of Bauchi State and current Emir of Zuru; Lt General (Dr) Ishaya Bamaiyi, former Chief of Army Staff (COAS/CODS), and the late Maj. General Musa Bamaiyi, former Commandant, NDLEA.

Others are Brig.-General Dauda Komo (retd), former Governor of Rivers State; the late Brig.-General Tanko Ayuba, former Kaduna State Military Administrator; the late Col. Sule Ahman, former Enugu State Military Administrator; and Maj.-General Muhammadu Magoro (retd), former Chairman, Nigeria Maritime Authority, etc.

Others are the late Mr Nathaniel Zome and Malam Ibrahim Mori Baba, both of whom became Postmasters-General (NIPOST); the late Alhaji Ladan Zuru, former chairman, NIWA, Lokoja; and Mr Ben Dikki, former Director-General, Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE). The trio of Amb. Nuhu Mamman, Amb. Kware, and Amb. Sunday Thomas Dogonyaro, at one time manned Nigerian embassies abroad.

Not to be left out are Justice Bala Zama Senchi, Barrister Maikyau, the President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA); the late Malam Usman Sani, former Minister of State; Professor M.K. Abubakar, former Federal Minister; HE Alhaji (Dr) Samaila Yombe Dabai, mni, former Kebbi State Deputy Governor; DIG Bala Zama Senchi, Deputy Inspector General of Police (NPF HQ Operations); and DIG Suleiman D. Fakkai, retd.

Discussing honours, it is the driving force of a Zuru man without which he does not only reincarnate as Okno but does not get a girl to marry and procreate to deepen his lineage and have his grave decorated with terracotta figurines and staff of achievement. And most of these titles and honours do not simply come from being blue-blooded but from brain and brawn in their lines of occupations which is rooted in their families but with honourable exceptions.

Some of these titles could be described roughly as Ch’werke, chief farmer; Ch’tagee, chief hunter; U’gamba, wrestling title; Gov’din Golmo, chief of Golmo Brigade; and Gov’din menke, chief rainmaker. The overall king is titled Gomo, which M.M. Gujiya (2014) alluded to Greenberg’s socio-linguistic classification of trends in similarities in both sound and meaning to further connect Lelna with the Kaduna–Benue-Plateau people.

He gave instances where they have same word formation among the Buta, Kurama, Kahugu, Gure and Kagoro. For example, he says, the word for God is referred by all the groups as Gure-Kashile; Buta-Shile; Kahugu-Kashiri; Lelna-Assile, etc. Similarly, the words for ‘Chief’ among the Middle Belters have the same bearing, thus: Lelna–Gomo; Gure–Gwom; Kagoro–Agwan; Birom-Gwom, etc. He further goes to reveal that the word for eat in C’lela, Kamumu, Tiv is Ya, while the word for five is Tan for both mentioned ethnic groups and so on.

The Zuru Emirate is principally peopled by the Lelna ethnic group with other sub-groups such as Fakkawa, Bangawa, Dukkawa and Katsinawan Laka. The Laka people, who mainly populate the Wasagu area, are said to be recent migrants from Katsina State who came in search of fadama for farming, trading and as war refugees.

Each group, however, has its own history of migration pattern either from the North-west or the Kwararafa and Nok zones. While colonial records showed their own bias, it is still not convincing and generally acceptable whole-heartedly. It is noteworthy that the Lelna are also said to be an autochthonous group in Alela as against what P.G. Harris thought. As another version has it that they were part of Hausa ethnic group from Katsina tracing it to around 12th-14th century arrival of Lamurudu, a Habe Hausa. Yet another version connected them with the Kwararafa movement out of the Middle East, Egypt and thence present day Northern Nigeria.

It is why one can explicitly agree here with the likes of B. Swai (1990) who also validated C. Ake’s assertion that the Nigerian historiography is not objectively written as it is flawed with bias from the political viewpoints of the traditional rulers, leading politicians and colonial overlords. The danger with the tendency is that history is written to validate dubious claims on the origin of state formation in order to legitimise the control and oppression of the minority ethnic classes. Zuru elders have, however, pointed out the linguistic, anthropological and archaeological evidences and connections with the Kainji speakers, a sub-branch of the platoid group of Benue-Congo speakers, e.g. Berom, Kamuku, Kambari, Jaba, Gbagi, Adara, Yargam, etc. Researchers have noted that many examples of these similarities can be seen in iron works, stone works, pottery, hunting, sports, religion, arts and rites of passage. The Lelna language has more in common with the Middle Belt ethnic groups’ history, culture and customs than with the Afro-Asiatic hermitic ethnic group.

Efforts have been made in the past by both egg-headed indigenes, scholars, missionaries and foreign researchers to document some aspects of Zuru Emirate’s history, culture, songs, orthography, poetry, etc. In this regard, mention must be made of Samuel Umaru, Benjamin Dikki, Danladi Senchi, Amos Sakaba, Michael Gujiya, Prof. Samuel Ango, Bawa Amos, Sani Sani, Philips Harris, Bulus Rikoto et al, A.R. Augie et al, Dettweiler Stephen, etc. On its part, ZEDS has done an enormous job of sponsoring the research and writing of Zuru history in 1990 under Nath Zome’s presidency.

All said, the tourism-loving Emir of Zuru is sure harnessing its potentials involving monuments, grotto, shrines and other ‘magnetic fields’ which adorn its landscape and mesmerise people. Additionally, it has spellbound festivals and celebrations which made the colonial officers to describe the people as merry makers. Probably, they were referring to Dibiti, Uhola, Yadato, Beledimo, etc., organised with double motives of thanks-giving and religious rituals. The Girmache grove is a popular crocodile sanctuary visited by tourists to either seek spiritual intervention, further their knowledge of ancient flora and fauna or appreciate cultural heritage. There are priests who attend to the pilgrims and culture enthusiasts. The sanctuary could well be approved as a heritage site and an arboretum to ensure its continued survival.

Zuru also boast of monuments and caves like the Zuen Gorge and Grotto, a waterfall and a historic burial ground of demised slave riding caravan and safe cave at Paeni which was used during imperial wars. Also available is the Tadud Wawanta Stone Monument at Rumu with its machete cuts inflicted by slave chasers. Information had it that the young lady had prayed to the god of the land to save her, hence her transformation. Her stone figure is now beseeched for intervention as patron saint of children and nursing mothers. There is also the Isgogo Slave Market, which still displays relics of Trans-Atlantic and Sahara slavery and tomb of a white slave merchant.

The concept of cannibalism is as old as man and was practised by all civilisations the world over with the exception of few veggies of the Indian descent. It is this predilection that produced omnivores or carnivores like some animals of which man is a part. In fact, notwithstanding moral psychology and cognitive dissonance has attributed individual and group’s values, emotions, cognition, attitudes and general personality characteristics as having something to do with power as against those meek characters who care less. And this is in tandem with cultural practices of masculinity and at the same time romantics.

Yesterday, Zuru people may be the rapacious lovers of meat, but not today. They cannot claim the prize of komai nama as civilization and urbanisation have enabled us to expand our knowledge of other ethnic groups’ culinary habits. For instance, we now know the Hausa love for suya, balangu, kilishi, dambun nama, ragadada, biscuit bone brisket or whatever, and the Yoruba love for ogufe, orishi-rishi, abode, isu, kpomo, tripe or offal, gbokoto, etc. The same goes for the Igbo who have special affinity with meat eating as a trophy that they have arrived. An Igbo individual can consume a whole goat-head in form of either eshiewu or nkwobi, or go for fried meat, stick meat, cow-leg, cow-head, cow-tail, etc. So, today the Zuru people cannot boast of being the highest meat consumers like before. Could it be that even then they weren’t the prize holders as all ethnic groups were also into the meat-eating frenzy but unknown to each other, because they all live in their little world?

* Dr Haruna Penni is a freelance writer based in Abuja. He is on 08034299585