The journey from Sokoto to Matazu was an adventure in itself. Anticipation would bubble within me as we set off.

Dutsen Kwatarkwashi (I nicknamed it Dutsen Intalan-Tiyante, a song from the tale of the hyena and the goat that I always imagined atop the rock) in Zamfara State, was a comforting sight. The winding roads, the dusty landscapes, and the vibrant markets along the way, all added to the excitement.

And lest I forget, the ever-mouthwatering meat pie from the famous Lalan filling station in Gusau. We’d often stop there on our way to or from Matazu, the flaky crust and savory filling a delightful treat.

Matazu, a town etched into my childhood memories, was once a haven of peace and tranquillity. The town, nestled amidst the sprawling landscapes of Katsina State, was a place where time seemed to move at its own leisurely pace.

The dawn was my favourite time of day. The sun would kiss the horizon each morning, casting long, dancing shadows through the pigeonhole window of my grandmother’s room. I’d lie awake, my imagination running wild, convinced that the tiny window was a shield against the mythical hyenas from the tales of Gizo Da Koki, lurking in the darkness.

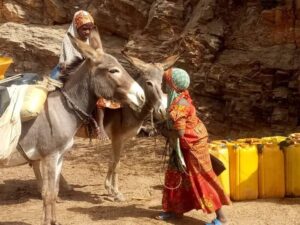

The village was a symphony of sounds. The rhythmic clinking of water being poured into clay pots, the gentle thud of millet being pounded, the cheerful bleats of goats and donkeys, all harmonised with the rising sun, creating a symphony that heralded the new day.

One of my favourite childhood memories was gathering around the fire with my cousins, to watch my aunt (Goggo Gaje), bake masa for breakfast. The smoky aroma that filled the air was intoxicating, and we’d eagerly take turns turning the cakes in the tanda, a traditional baking pot. The anticipation of the first bite was almost unbearable.

With my cousins, I’d explore the nearby river, its sandy banks a playground for our adventures, digging a rijiyar kwakware (sandpit), building a ɗakin kurciya (mud hut), and gather clay for moulding our play pots and beds. We’d pluck mangoes from the orchard, their sweet juices a refreshing treat.

As the sun dipped below the horizon, our faces lit by the flickering flames from the hurricane lamps, my grandmother would regale us with tales of Maikilago, a mischievous water spirit who lurked in the depths of the river. The stories, filled with magic and wonder, ignited our imaginations and kept us captivated for hours.

The moonlit nights were filled with the sounds of laughter, ina-jan-i-na jan-je, and the occasional whispered fear of the mythical creature.

Market days were grand affairs. The town market was a vibrant spectacle, filled with colourful beads, intricate fabrics, and the sweet aroma of freshly fried kosai, tsire, and spices. I would help my cousin, Mairo, sell her kwalbebe, a refreshing, sweetened, and tangy drink made from baobab fruit, measured out using bottle crowns.

Village celebrations were a joyous spectacle. The dancing at the arena was a whirlwind of energy, girls dancing in rhythm to the kalangu and kukuma music. Weddings were particularly memorable, culminating in the wankan amarya tradition, where the bride was seated on a mortar in the centre of the courtyard and bathed with henna and perfume.

Matazu was a sanctuary, a place where time seemed to slow down. The days were filled with laughter, play, and the simple pleasures of village life. When the holidays drew to a close, the sadness of leaving was palpable. Returning to Sokoto meant bidding farewell to the carefree days and facing the realities of city life.

My mother would greet us with a mixture of relief and concern. She’d treat the head lice and boils I’d inevitably acquired from drinking unfiltered water, but I’d shrug it off, more preoccupied with the memories I’d made. The village was my escape, my happy place, and nothing could dampen my spirits.

Today, Matazu is a far cry from the peaceful village I remember. The threat of banditry has cast a dark cloud over the region. My heart aches for the people of my village, forced to live in fear. I yearn for the day when peace returns to Matazu, when children can play freely and adults can go about their lives without the constant threat of violence.

It is imperative that peace and stability return to the northern part of Nigeria and other affected regions of the country. Only then, we can live our lives without fear and reclaim our rightful place in society.

* Halima Ahmad Matazu is a lecturer at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) headquarters in Abuja