It is curious why the late Chinua Achebe missed the Nobel prize for Literature in his life time. Not only was he the most widely read African author, but his works, particularly his debut novel, Things Fall Apart, published since 1958, has been translated into more than 50 world languages. The novel was, indeed, one of the first creative strategic missiles by an African intellectual that hit the European colonialists with their arrogance of a superior culture.

The next significant African novelist to assault the Empire was the Kenyan Marxist, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, whose works do not only repudiate imperialism but defy the capitalist ideology of the European countries. He is still alive, but he too seems to be waiting in vain for the Nobel. You do not throw punches at the colonialist or question his bogus claim for a superior, universal culture and expect to be rewarded by him.

In this wise, the legendary Wole Soyinka is luckier. His plays, poetry and fiction are less combative than the works of the other two or, more appropriately, less accessible to the average reader. His intellectual oeuvre intimidates even the most cynical of Europeans and compels them to accord Kongi his rightful place at the hall of fame.

African literature is so far basically driven by resistance and agitation. Our writers crusade against cultural domination, corruption, as well as political and economic marginalisation. Being conscious of the complexes and denigration of the past, slavery and slave trade, colonialism and arbitrary creation of new nation states in Africa by the Europeans, most African writers are committed towards restoring the dignity of Africa and its people.

Just when it appears as if Africa was completely liberated, there arises a new form of seemingly benevolent domination. Policies of globalisation manifesting in form of massive armament, global media invasion, prohibitive IMF/World Bank initiatives and so on perpetually keep African nations in check.

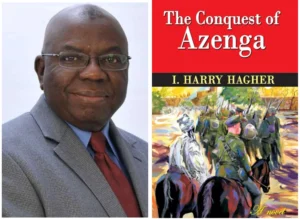

However, the recent publication of Professor Iyorwuese Harry Hagher’s novel, The Conquest of Azenga, has introduced a different trajectory in the fight against imperialism. Hagher’s punch is unique. Achebe and Ngugi wrote essentially about African characters and how they respond to the destruction of their culture and annexation of their territories. That, of course, required some panel-beating or some measure of romanticisation of African culture to give the desired effect. This definitely leads to self-abasement, an attempt to apologise for or hide in felicity in one’s culture.

It is often said in military parlance that the best form of defence is attack. Hagher adopts this strategy and takes the battle to the footsteps of the coloniser himself. His main characters in the novel are not Africans but white Europeans.

Sir Lord Payne, the arrowhead of the British colonial administration in the novel, is a reenactment of Sir Lord Lugard, the first Governor-General of Nigeria. Other equally significant white characters are picked from both the secular and church administrators on civilising or evangelising missions among the Tiv, fictionally referred to as the Azenga, to expose the hypocrisy, greed and vulnerabilities of the Europeans.

By so doing, Hagher’s novel avoids the pitfall of giving excuses for the so-called primitivity of African culture. It reverses the postcolonial panopticon in such a way that it is now the victims of subjugation that torment the oppressor with superior moral censure.

The idea of the white man teaching his colonial subjects morals or looking down on them condescendingly is now reversed. There is a tit for tat. Joseph Conrad, in The Heart of Darkness, creates African savages who are criminals, enemies and cannibals. Hagher’s The Conquest of Azenga creates British savages who are brutish, inhuman, but cowardly.

The moral compass of the Tiv (the Azenga) undermines the imperialist agenda which is predicated on theft and economic exploitation and their diabolical agenda of transferring such privileges to a local nomadic tribe, the Kilans, who exemplify the Fulanis in the novel.

In the Azenga society, however, Lord Payne meets a group of people that are inherently decentralised, republican and circumspect, who would neither surrender to white colonialists nor the indigenous monarchs of tribes set over them. The novel covers a wide range of historical occurrences in both colonial and post-independence Tiv land with lucid and sometimes scatological details, all to prove the unwholesome conditions the minority tribes were subjected to by both foreign and indigenous imperialism.

I find Professor Hagher’s novel so refreshing and hugely successful. The idea of culture conflict or European domination and struggle for independence is an over-flogged theme in African literature. It takes an exceptionally brilliant writer to navigate it in the 21st century with the kind of renewed interest Hagher has done in an excellent psychoanalysis. Let’s celebrate him even if the European community may again shun such a writer of genius.

I recommend the novel, The Conquest of Azenga, by Professor Iyorwuese Harry Hagher, for all of you to read.

* Professor Terhemba Shija, a former Member of the House of Representatives, is a poet, novelist, critic and politician. He lectures at the Nasarawa State University, Keffi