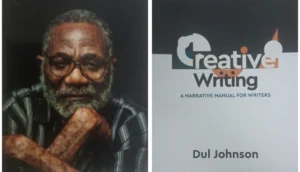

It is generally believed that a writer is born not made. In this book, Professor Dul Johnson re-affirms the belief and emphasizes that the born writer could enhance his talent by learning the necessary skills.

He makes the point in the introductory part of the book thus: “I was not taught creative writing. There was no formal or informal class of any kind for me. If I was ‘taught’, it was the indirect introduction to it through reading; the encouragement to read stories and plays by my teacher in secondary school, which had built upon the indirect lessons taught by storytellers of my childhood” (page ix).

On the formal acquisition of literary skills in addition to the talent, he says, “I discovered the art of creative writing in a Stylistics class during my undergraduate studies. The course was taught by an inspiring young man at the time, Munzali Jibril, who was to become an erudite Professor of English, and one of Nigeria’s best” (page ix).

This book is, therefore, a result of the author’s belief in the teachability of creative writing and his thirty years of teaching that has improved many students, some of whom have become great writers and award winners.

The 113-page manual contains ten chapters discussing various aspects of creative writing, providing the how-to. The topics include ‘Qualities of a Writer’, ‘Story Development, ‘Character and Characterisation’, ‘Conflict and Suspense’, ‘Description and Narrative’, and ‘Rewrites, editing, proofreading’.

The author has brought his many years of teaching experience to bear on the work in a way that makes it learner-friendly. In keeping with the style of writing manuals, the instructions are direct to the point and conversational, with practical exercises that further make it interactive.

In the first chapter, he identifies three types of stories: bad, good, and great stories, noting that the bad ones are poorly plotted, badly narrated and have nothing to offer the reader to entertain them or give them a message to take home, and usually come from one who has neither talent nor skill but tries to write.

Good stories have a fairly long shelf life because they offer both entertainment and a take-home value, and come from writers who have learning, or modest talent, or both. Great books, on the other hand, are written by people with a huge talent who may or may not have had any learning, formal or informal. Such stories are usually loved by many because they would find a piece of their life in it.

He concludes by affirming that, “With a great effort, a good writer can produce a great story. If you cannot become a great writer, aim at being good, for, it is to them that the industry belongs” (page 3). He then delves into discussing the topics blow by blow, beginning with the basic human qualities that a writer needs to acquire in order to stimulate his imaginative faculties.

According to him, the writer must be a good reader, a keen observer, a good researcher, hardworking, humble, and have a little bit of craziness.

He prescribed the materials to read: “It is okay to read bad stories in order to learn how not to write, but my charge to you is to read hundreds of well written storybooks; great stories, if you can. Reading should not be limited to [good] books, however. Newspapers, magazines, comics, etc. Watching films and television. All of them are forms of storytelling and experiencing them is a form of reading” (page 3).

The author stresses the need for the writer to be observant because good stories thrive on details, and observation helps one to see details in life; specifics that range from the external environment to the internal being of humans.

The author also discusses an interesting angle to the qualities of a writer which is less talked about – a dose of craziness. A little bit of abnormal thinking, he says, creates something extraordinary.

“Crazy imaginative thinking is not the cheap thinking outside the box. No! it is thinking inside the box and bursting the box open to be able to walk freely. It is planning against the grain of the wood in order to make the wood different and more functional.

“It is intentional aberrational thinking to prove that there is always another way to look at something. It is the destruction of conventional thinking to make the reader think beyond the story” (page 16).

Pages 17 to 26 are dedicated to instructions on some exercises and games the writer could use to stimulate his emotions, thoughts, and imagination to be converted into story ideas and elements such as mood, tone, imagery, symbolism, narrative, character, etc.

The games include Fixed Focus Observation, Free Focus Observation, Blindfolded Imagination, Blindfolded Listening, and Visits to Spooky Places. The games may sound crazy, but they have been tested and proved effective, according to the author. Fixed Focus Observation, for instance, helps the writer’s description and narrative powers.

The Fixed Focus Observation game involves, among other moves, fixing your head in a position for 5-10 minutes without letting your eyes move left or right, capturing everything in that frame of focus as a picture or movie clip. Then, leave the scene and reproduce on paper what you saw physically and what you saw in your imagination; things that were actually there and those that came into existence only through your imagination.

Through constant practice, this intentional focusing becomes a part of the writer, enhancing his ability to focus and easily source or create story ideas and plot them effectively.

In the subsequent pages, the author discusses the processes involved in storytelling: idea, storyline, and plot. He asserts that every piece of creative writing starts from these three items. “Idea gives birth to the story, which only presents itself at this point as a storyline or plotline. The plotline is not the same thing as the plot… The plotline provides the superstructure on which the plot is built” (page 28).

He discusses the processes and how the writer should handle each process to turn his thoughts into something concrete.

Character development, conflict, description, and narrative are among the writing skills discussed by the author. According to him, great stories, whether they are found in dramatic or prose writing, are a product of great thinking and the interplay between character and conflict.

He defines conflict as the clash of interest or interests, a sustained threat to the character’s interest, from within or from an external entity such as a person, thing, society, or force.

He stresses that understanding character and conflict are indispensable requirements for a good story. “In fact, without character, there is no story, and without conflict a story would not be worth reading” (page 48).

Emphasising the importance of conflict, the author says it is the single major source of suspense, which makes “us sit on the edge of the chair, or stand up and walk to the window as if the answer to the question on our minds were out there, or make us close our eyes for a moment and imagine what is happening to the character we are empathizing with” (pages 63 – 64).

In Chapter Ten, the concluding chapter, the author stresses the importance of rewrites, editing, and proofreading, saying great stories do not only take time to conceive, plan, and write, but they also require lots of these final aspects as they are the secret to successful writing.

He concludes with an important message on breaking literary conventions to add a touch of novelty to a story. The topic is titled “Parting Words on Writing Conventions” and covers pages 109 to 113.

This is the crux of the idea: “Rules are made to be broken. But they must be broken only by those who have mastered the rules, so that when you break them, everyone can see, not only the beauty in your breaking the rule, but also the beauty of the new one you have created” (page 110).

Creative Writing: A Narrative Manual for Writers is indeed a valuable handbook for both aspiring and ‘old’ writers interested in honing their skills. It contains so much valuable information and easy-to-imbibe instructions.

Such excellent work is only to be expected from the author, considering his wealth of knowledge and experience in the field.

Professor Dul Johnson, an erudite scholar, writer, literary critic, and filmmaker, has been teaching creative writing since 1995. He began his career as a drama director with the Nigerian Television Authority, Jos, where he worked for many years before retiring into independent filmmaking and teaching.

His best-known films include ‘There is Nothing Wrong with My Uncle’ (a cultural documentary), ‘The Widow’s Might’ (a feature film), ‘Against the Grain, Wasting for the West’, and ‘Basket of Water’.

His independent movie, ‘The Widow’s Might’, won an award at the 2002 Pyonyang International Film Festival, and his documentary, ‘There is Nothing Wrong with My Uncle’, was nominated for best documentary at some international film festivals, including the 8th Africa Movie Academy Awards and nominated for Best Documentary at the Basil Davidson Ethnographic Documentary Festival, 2013.

He has authored many literary works in short stories, novels, poetry, plays, biography and journalistic writings. They include Shadows and Ashes, Why Women Won’t Make It to Heaven, Deeper into the Night, Across the Gulf (winner of ANA fiction prize for 2017), When Dreams Burn (winner of ANA Abubakar Gimba Prize for 2023), Ugba Uye: The Living Legend, Melancholia, and In the Crucible.

Professor Dul Johnson is currently lecturing at Bingham University, Abuja.

* Sumaila Isah Umaisha is on the staff of Primary Health Care Development Agency, Abuja